Investing in International Stocks

February 2012 Client Letter

Last year was an unpleasant year in global equity markets. Modest gains in the S&P 500 (+2%) masked steep declines in most equity markets throughout the world. Of the 23 developed equity markets, only two were up in 2011—the U.S. and New Zealand. Of the 21 markets that fell, 17 were down double digits, with a handful of those down more than 20%. Emerging equity markets fared even worse. Of the 25 emerging equity markets that Young Research tracks, only three finished the year in positive territory. Close to half of the world’s emerging stock markets fell more than 20% in 2011.

But the dismal performance of the world’s equity markets in 2011 has been relieved by a powerful global stock market rally to start 2012. As of this writing, the S&P 500 is up 9% with many international markets rising even more. In U.S. dollar terms, the German stock market is up more than 20%, and Brazil’s equity market—one of last year’s worst-performing markets—is up an impressive 25%.

The performance reversal in global equity markets is a testament to the virtues of taking a long-term approach to investing. Investors who abandoned losing positions during the worst of the market collapse last year most likely forfeited substantial gains this year. Of course, taking a long-term approach is easier said than done. This is especially true when volatility and uncertainty are elevated, as they have been over recent years. To remain confident and comfortable with a long-term approach, it is useful to know what you own and why you own it. This month’s letter takes a look at a few of our favorite investment themes and companies. Brazil has long been our favored emerging market economy. Our investment thesis on Brazil is focused on the country’s long-term potential. We believe Brazilian shares have strong secular tailwinds working in their favor. Brazil is a middle-income country moving rapidly toward developed market status. Economic growth in Brazil has outpaced growth in the developed world, and we see very little on the horizon that points to a change in this trend.After years of rapid inflation and economic instability, interest rates in Brazil are sky-high. But past mistakes have seemingly been taken to heart by Brazil’s policy makers.

Current leadership appears not to want a repeat of the hyper-inflation that plagued the country in decades past. As a result, we expect a long-term secular decline in Brazilian interest rates. Falling interest rates are often bullish for equities. During the 20-year secular decline in U.S. interest rates, the S&P 500 rose at a compound annual rate of 18%. Looking at the year ahead, we believe a more accommodative monetary policy, a recent credit-rating upgrade from Standard & Poor’s, and the suspension of a tax on foreign equity investments point toward further gains in Brazil’s stock market.

CEMIG

To gain Brazilian equity market exposure, we purchase both Brazilian ETFs and common stocks. We are currently buying two small-cap Brazilian ETFs. We buy Brazilian small-cap ETFs because they provide more direct exposure to Brazil’s domestic economy than large-caps. Our largest Brazilian common stock position is Cia Energética de Minas Gerais (CEMIG). CEMIG is Brazil’s third-largest energy generation and transmission group and the largest energy distribution group in Brazil. CEMIG controls 65 generation plants, 59 of which generate electricity from the most economically viable renewable energy source—hydroelectric power. CEMIG has total generating capacity of 6,925 gigawatts. In our view, CEMIG also has strong growth prospects for a utility. Over the last five years, electricity consumption in Brazil has risen at a 5% compound annual rate. CEMIG shares currently yield 5% and offer the prospect of moderate long-term growth.

Like CEMIG, Canadian-based Brookfield Renewable Power is a big hydroelectric power producer. In our view, hydroelectric power producers have appeal to long-term investors. Hydroelectric power plants are a low-cost renewable source of energy. Hydro plants have long lives, low maintenance requirements, strong reliability, and no high-heat combustion to wear down equipment. Brookfield Renewable Energy recently completed a merger with Brookfield Renewable Inc.—a related company. The combined companies offer investors strong long-term dividend growth prospects. The new Brookfield is one of the world’s largest publicly traded, pure-play renewable power platforms. Its primarily hydroelectric-generation portfolio includes 170 hydropower facilities and five wind farms, and totals approximately 4,800 MW of installed capacity, including projects under construction. Its portfolio is diversified across 67 river systems and 10 power markets in Canada, the United States, and Brazil, and generates enough electricity from renewable resources on average to power two million homes annually. With a fully contracted portfolio of high-quality assets and a significant pipeline of projects and growth opportunities, the business is positioned to generate stable, long-term cash flows, supporting regular and growing cash distributions to investors. Brookfield Renewable shares currently yield 5%.

Statoil

We also favor Statoil (STO). Statoil was formed by Norway in 1972 to exploit the massive reserves of oil and gas on the Norwegian continental shelf. After going public in 2001, Statoil has grown to be one of the world’s largest energy companies, with a market capitalization of over $84 billion. Today, Statoil is the second-largest natural gas supplier in Europe and the world’s sixth-largest. Statoil is also a world leader in subsea technologies, with the largest number of subsea wells at ocean depths lower than 100 meters. Statoil shares yield 4.25%.

Statoil is one of a handful of European stocks that we own—none of which are based in the euro-area and all of which are multinational companies. While the European Central Bank has stabilized the euro-area debt crisis by dumping massive amounts of liquidity into the financial system, risks remain. As we have long maintained, liquidity is not the underlying

problem in the euro area. The liquidity crisis last year in Europe was a symptom of solvency concerns, which were in turn caused by the currency union’s flawed design. Varying levels of competitiveness between countries that share the euro are the underlying cause of the region’s problems. Competiveness is not something that can be easily improved. Consequently, we continue to view the euro area cautiously and, for now, we are still avoiding euro-area stocks.

We are, however, investing in non-euro-area Europe. Switzerland remains one of our largest European positions. We recently made some adjustments to our client’s Swiss holdings including the sale of our remaining position in the Swiss franc. Several months ago the Swiss National Bank (Switzerland’s central bank) made a decision to peg the franc to the euro. While the peg may be removed at some point in the future, until it is, a position in the franc is effectively a position in the euro.

Investing in ABB

We also initiated a position in Swiss-based ABB. Tracing its roots back to 1883, ABB provides power and automation technologies to utility and industry customers worldwide. ABB invented and pioneered many power and automation technologies. In 1952, ABB built the world’s first high-voltage direct current (HVDC) power connection to increase the efficiency of electricity transmission. In the 1990s, the company introduced HVDC for underground transmission. ABB’s portfolio of products ranges from light switches to robots for painting cars to electrical transformers and control systems that manage entire power networks and factories.

ABB’s end markets offer attractive long-term growth prospects. Growing emerging market demand for electricity, widespread government support for energy efficiency, and an aging electricity infrastructure in developed markets point toward consistent long-term demand for ABB’s products and services.

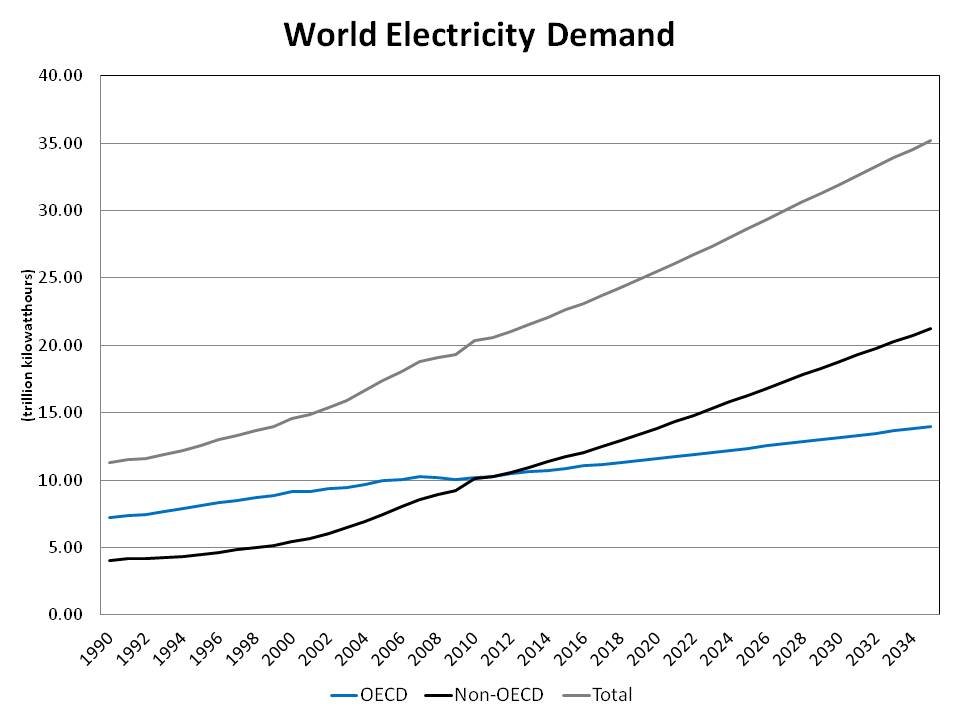

Emerging markets, the source of almost 50% of ABB’s orders, are projected to double electricity demand by 2030 and triple it by 2050. As incomes grow in emerging markets, more people move to cities and towns, driving up the demand for electricity. According to Goldman Sachs, a 1% increase in the number of people living in cities leads to a 1.8% increase in demand for electricity. And a 1% rise in income per head leads to a 0.5% increase in demand. Urbanization rates and per capita income in many of the largest emerging markets are only a fraction of what they are in the U.S. The potential here is enormous. Our chart, titled Electricity Demand, shows the projected demand for electricity in OECD (developed) markets versus non-OECD (emerging) markets. ABB shares pay an estimated yield of almost 4%.

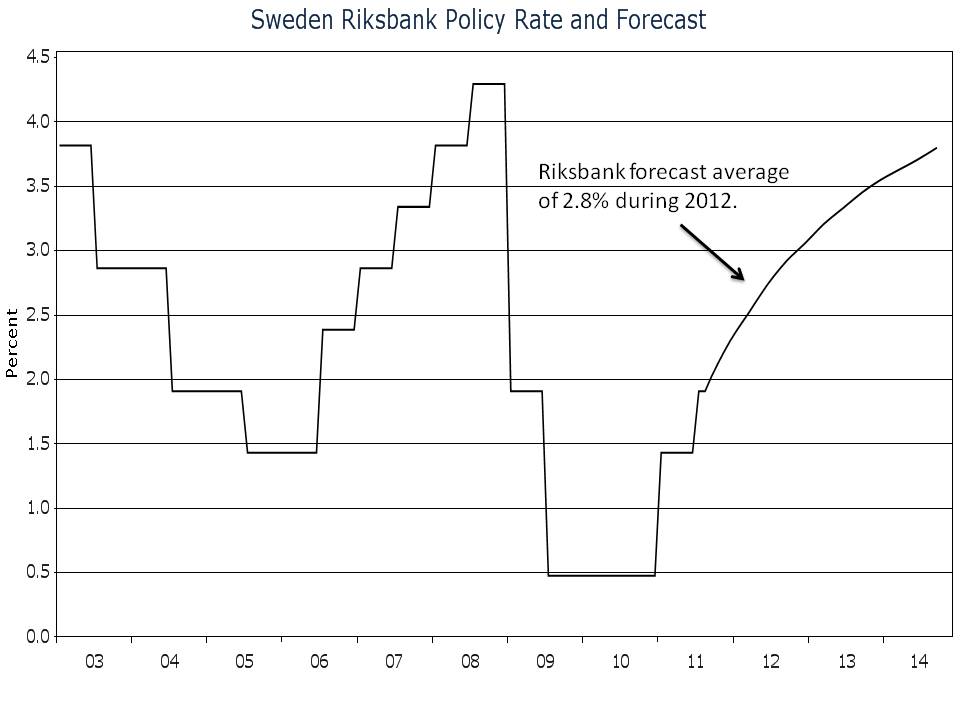

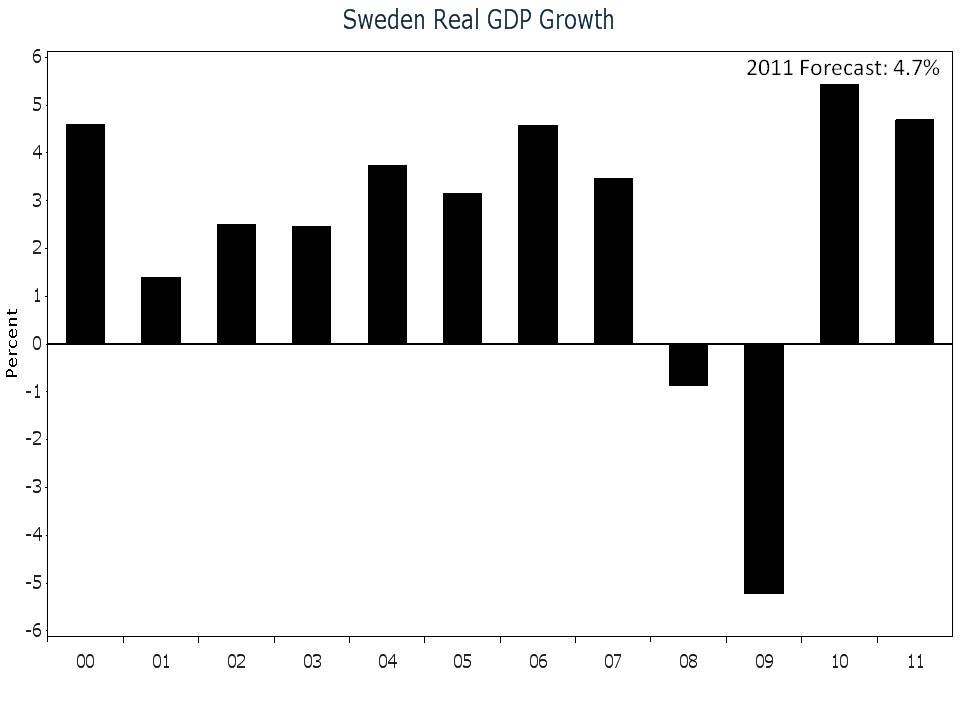

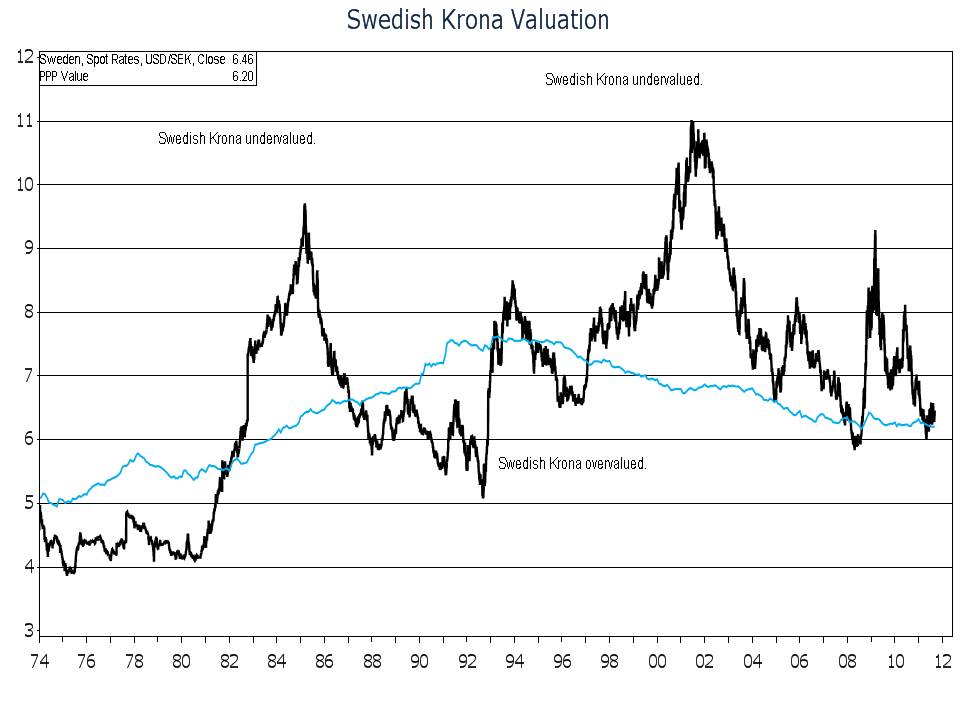

Another European market we favor is Sweden. In many portfolios we recently purchased a position in iShares Sweden. What do we like about Sweden? Among other factors, Sweden is the world’s third most competitive nation, a neutral country, and a true AAA credit with a government debt to GDP ratio of about 30% compared to over 100% in the U.S. Some of the top holdings in iShares Sweden are Hennes & Maurtiz, Ericsson, Volvo, and Svenska Cellulosa (SCA).

Vodafone & British American Tobacco

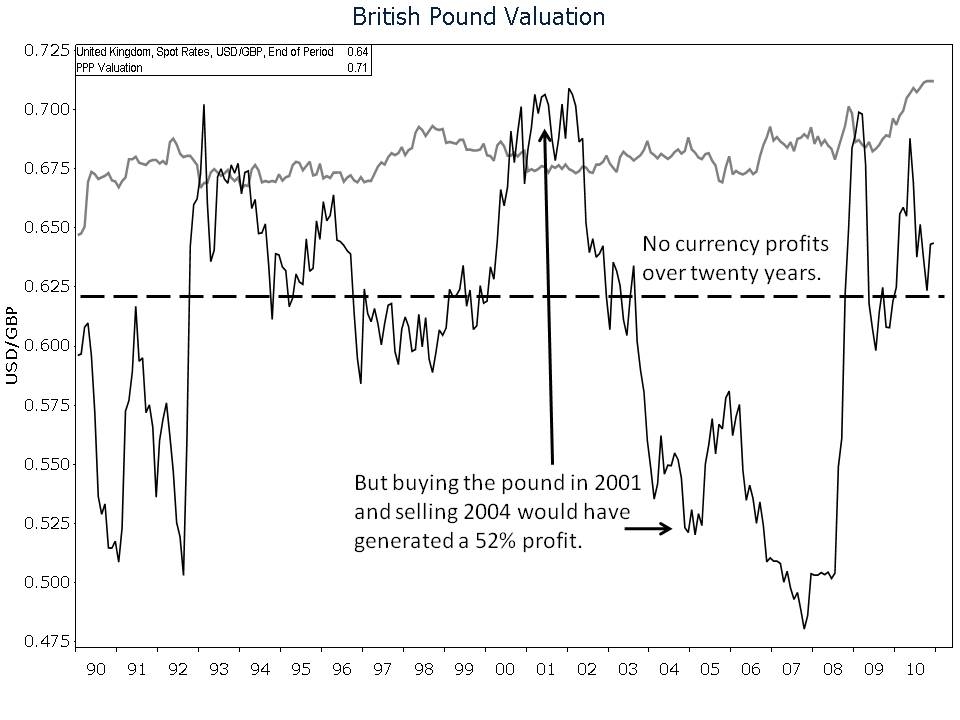

Two other companies domiciled in non-euro Europe that we have added to portfolios are Vodafone and British American Tobacco. Vodafone is one of the world’s leading diversified telecommunications operators. The company is one of the largest carriers of mobile voice traffic in the world, serving more than 370 million customers in 60 different countries. Vodafone has a significant presence in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia Pacific, and the United States through its 45% ownership interest in Verizon Wireless. Vodafone is positioned comparatively well among telecommunication companies (especially U.S. telecoms) to thrive, as the transition from fixed line to mobile voice and data continues. Did you know that mobile calls now account for 82% of all calls made globally? Vodafone’s fixed line business accounts for only 8% of revenue. The remainder of the firm’s revenue comes from mobile voice (64%), messaging (12%), data (12%), and other sources (4%). Industry-wide, about 40% of revenue comes from fixed-line services.

There are opportunities for Vodafone to increase revenue in developed markets. In Europe only 22% of Vodafone’s subscribers have smart phones compared to 40% in the U.S. The proliferation of tablets, and mobile broadband sticks, along with expanding 4G networks that offer download speeds comparable to cable, present compelling opportunities for Vodafone’s data business.

Mobile data is the fastest-growing part of the wireless industry. Industry-wide, data now accounts for 13% of revenue, up from 3% in 2006. By 2014, data is expected to account for 21% of revenue. In 2010 Vodafone’s mobile data revenue rose 26.4%. Based on dividend estimates for 2012, Vodafone shares yield a compelling 7.7%. What’s more, the board of directors has a medium-term dividend growth target of 7%. With a 7.7% yield and the prospect of meaningful dividend hikes in the future, what’s not to like?

The high level of regulation and taxation in the tobacco industry, as well as stagnant demand and litigation risk create high barriers to entry. The high barriers to entry give existing firms pricing power and allow them to remain unusually profitable. British American Tobacco is no exception. British American Tobacco, founded in 1902, today is one of the world’s largest tobacco companies. The company generates billions in free cash flow, with much of that cash flow coming back to shareholders in the form of dividends. British American targets a dividend payout ratio of 65%. The dividend has been increased every year since 1998 and over the last five years dividend growth has averaged 19.5%. Today, the shares yield 3.8%.

The performance of last year’s global equity markets offers investors at least two important reminders. Number one, it can pay to be patient. Many of the global equity markets that were down last year have enjoyed a nice rebound in 2012. Regardless of share price, investors can take comfort knowing they are receiving a consistent dividend payment when investing in the Vodafone and British American Tobaccos of the world. Number two is the continued degree of volatility in the global markets. We do not view this year’s stock market rally as anything but a respite from the many risks that continue to exist. We see problems ahead in terms of inflation, dramatically higher interest rates, dollar debasement, and market declines.

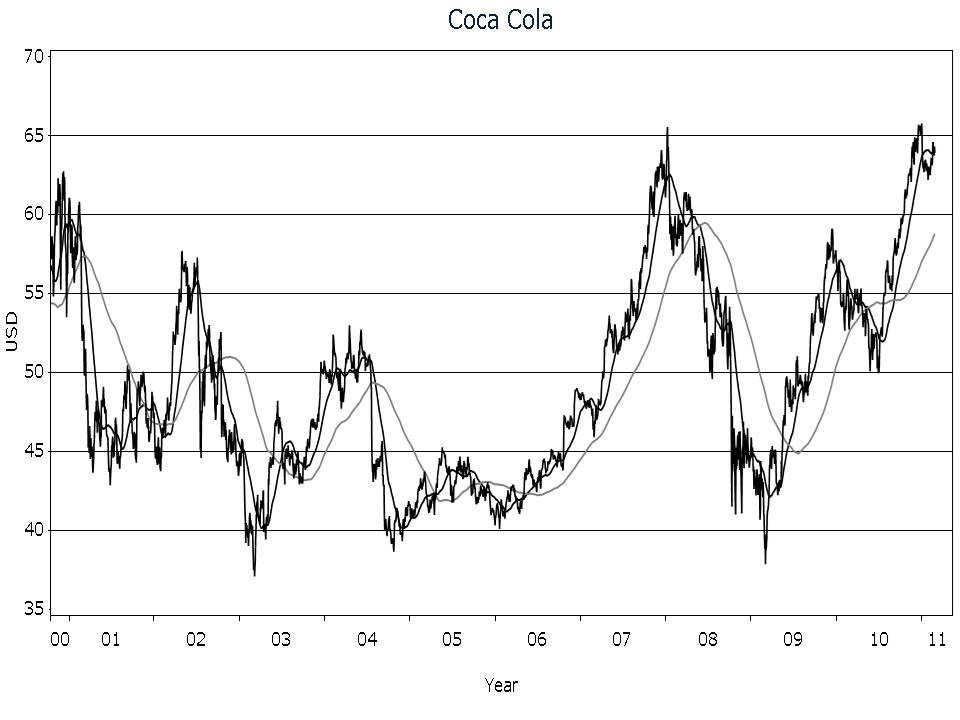

Our strategy with the purchase of equities continues to focus on what we believe to be big, durable, and lasting businesses. We invest in businesses with the potential to ride out economic downturns, distribute dividends, and raise those dividends annually. Ideally, these companies have strong balance sheets, pricing power, and operate in industries with high barriers to entry.

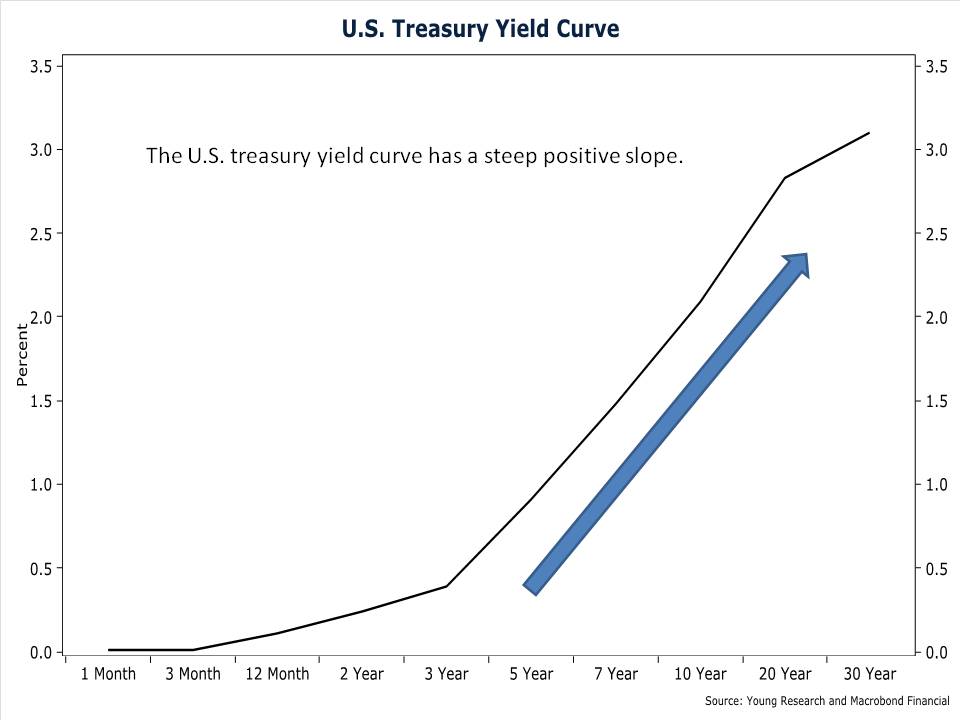

To complement the equities portfolio, we also favor bonds, gold, and foreign currencies. We appreciate the lack of enthusiasm investors have toward today’s bond yields. We are also frustrated with the Fed’s continued policy for a low-yield environment. But, bonds offer important diversification away from the stock market, helping to reduce portfolio volatility. Our bond portfolio tends to focus on shorter-term corporate bonds, which should limit volatility during a rising rate environment. We initiated our gold position in 2005 due to concerns about a declining U.S. dollar. As long we have dollar concerns, I expect us to maintain our gold and foreign currency positions.

Have a good month, and as always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Sincerely,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. Kimberly-Clark (KMB) has been in business for 140 years. Today nearly one-quarter of the world’s population buys KMB products each day including Kleenex, Scott, and Huggies. On February 28, KMB raised its dividend by 5.7%–the 40th consecutive increase. With a 4.1% yield and a consistent record of dividend increases, KMB is an ideal stock for our dividend-paying equity portfolio. Not as well known to most Americans is Sweden’s Svenska Cellulosa (SCA). We view SCA as the Kimberly-Clark of Europe. The company develops, produces, and markets personal care products, tissue, packaging, and forest products. SCA is the worldwide leader in incontinence care, the Nordic region’s leading diaper supplier (with 60% market share), Europe’s second-largest producer of corrugated board and containerboard, and one of the largest producers of corrugated board in China. SCA is also Europe’s largest private forest landowner with 6.4 million acres of forest. SCA is a basic consumer products company with valuable timber assets, and a strong balance sheet, trading at 12.5X earnings and paying an almost 4% dividend yield. What’s more, SCA has increased its dividend in 14 of the last 16 years. Over the last 10 years, dividends have compounded at an annual rate of 4.5%.

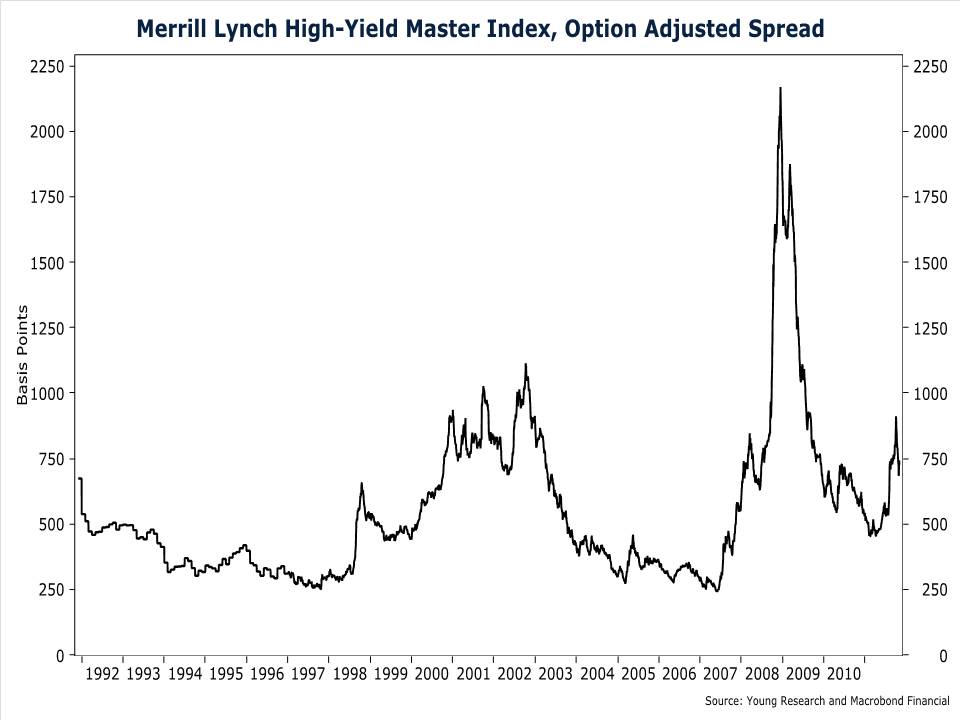

P.P.S. Next month I’ll preview some strategy adjustments we are making to fixed-income portfolios. In a yield-starved environment with economic data currently improving, the high-yield bond sector may offer areas of opportunity.

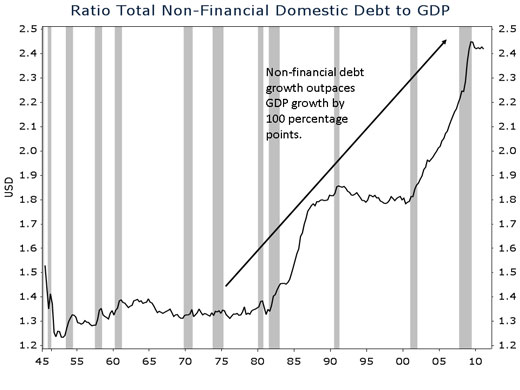

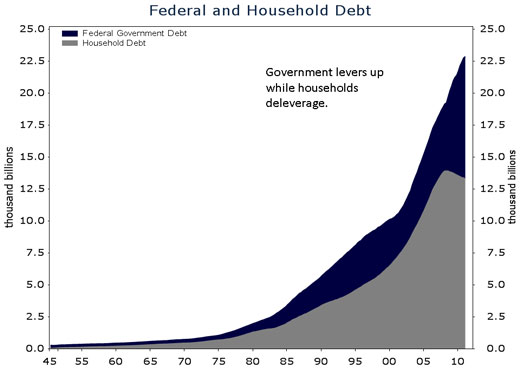

P.P.P.S. With the Federal Reserve pumping trillions of dollars into a global monetary system already soaked with liquidity, inflation is and will continue to be the result. For retired and soon-to-be-retired investors, the future inflation outlook should be alarming. Inflation is a destroyer of wealth—it’s compound interest in reverse. Owning commodities and hard assets that increase in value along with inflation may help. Owning stuff that’s in the ground can protect investors from a loss of purchasing power. As mentioned in this letter, Brazil and Canada are two countries we favor due to their wealth of natural resources.