Investors Facing an Unusually Uncertain Environment

October 2016 Client Letter

Investors Facing an Unusually Uncertain Environment

Today, investors are facing an unusually uncertain environment. We have a polarizing U.S. election whose outcome could have profound implications for the country and financial markets. The U.S. economy is far from robust and, in our estimation, is in the late stages of the cycle. Geopolitically, there is a broadening quagmire in the Middle East, coupled with increased hostilities with Russia, China, and now the Philippines.

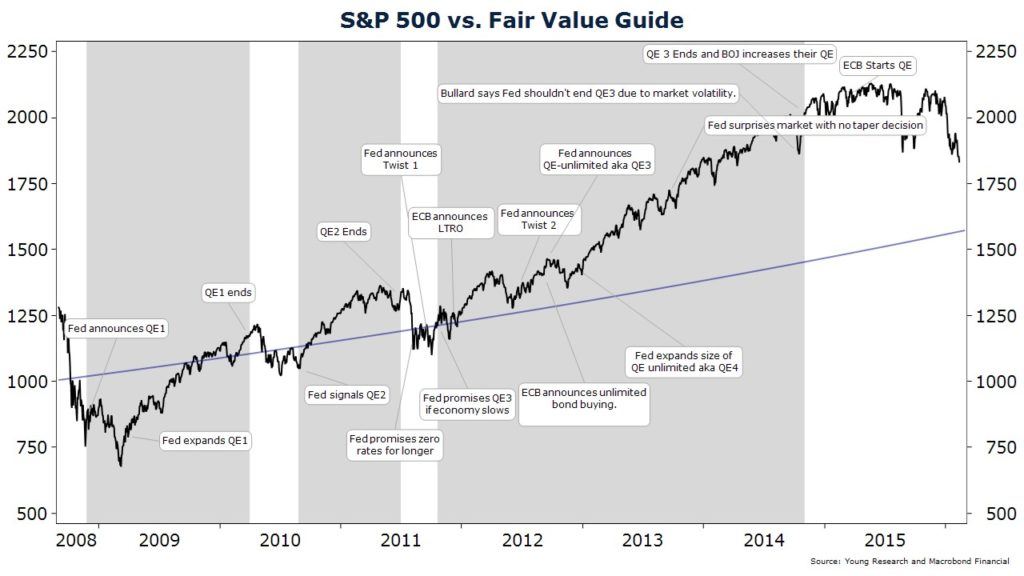

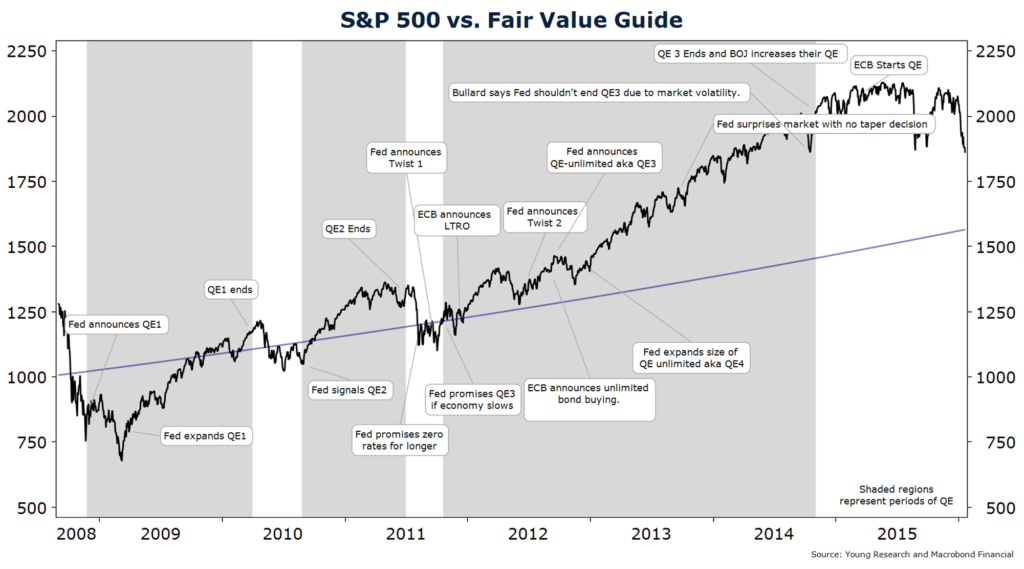

And that is just for starters. Investors are threatened by a sustained period of asset-price distortion and manipulation. The world’s central banks are establishing interest rates at artificially low levels, while at the same time pumping trillions of dollars of liquidity into the global financial system.

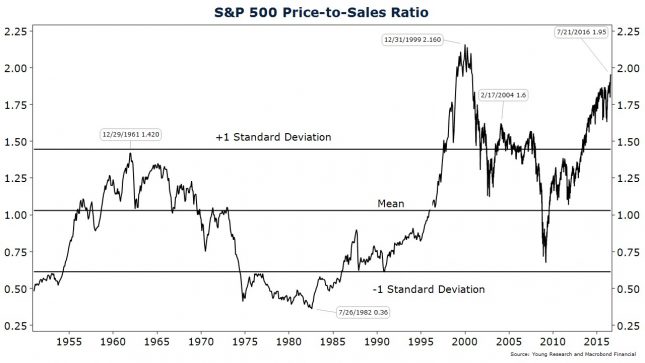

What is the likely outcome of a prolonged period of zero rates and trillions worth of ongoing asset purchases? In terms of the real economy, we will probably see more of the same disappointing results. In terms of the financial markets, zero rates and trillions of dollars in bond buying have ignited another massive reach-for-return environment.

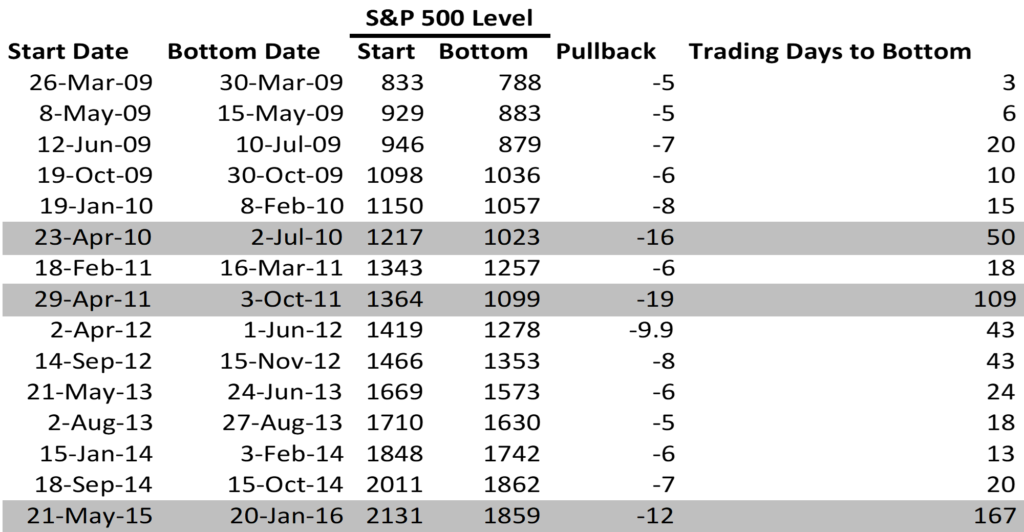

This doesn’t paint a pretty picture, in our view. The last two periods of excessive stock market valuation didn’t end well. And, we are concerned that the unprecedented monetary policies used to elevate asset prices have created a mirage of calm in what we see as a problematic environment.

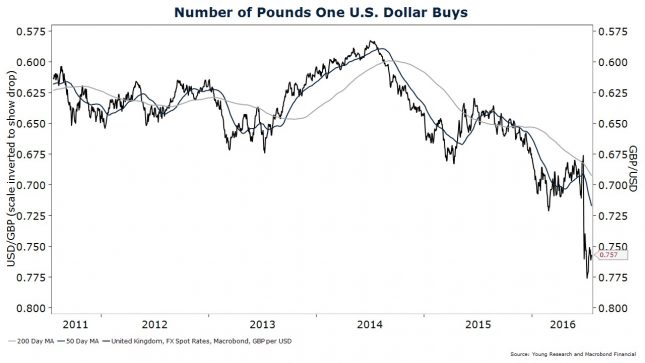

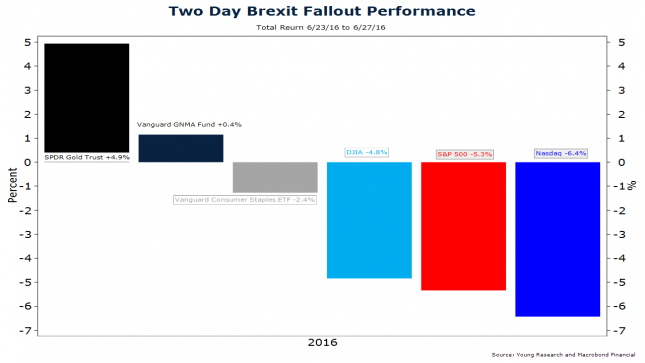

This summer we were reminded of how quickly markets can sell off. In a surprise vote on June 23, the British decided by a 52% to 48% margin to exit the European Union (EU). The vote caught many investors and pundits off guard. Financial markets cratered on the news, with U.K. stocks falling 16% and euro-area shares dropping 13%. The British pound fell over 13%, and government bond yields hit new lows. In the U.S., 10-year Treasury yields dropped to 1.36%—the lowest level in history.

Many clients share our outlook, and many prospective clients join our family-run firm because they are more comfortable with an investment strategy that incorporates a risk-first approach. Most of the portfolios we craft are designed to deal with what we see as a high-risk, high-uncertainty environment.

How Do We Invest for Clients?

How do we invest for clients to navigate a high-risk, high-uncertainty environment while still generating a steady stream of income?

We invest primarily in individual securities. While exchange-traded fund (ETF) model portfolios seem to be the strategy du jour, at Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., we emphasize individual securities more so than in the past. While we continue to purchase ETFs and mutual funds, both play only a supporting role in client portfolios.

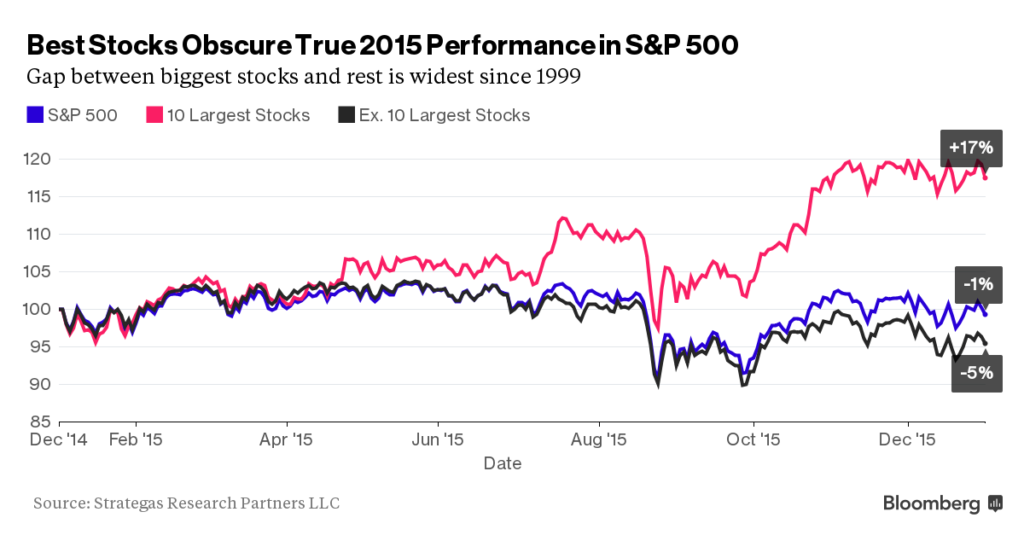

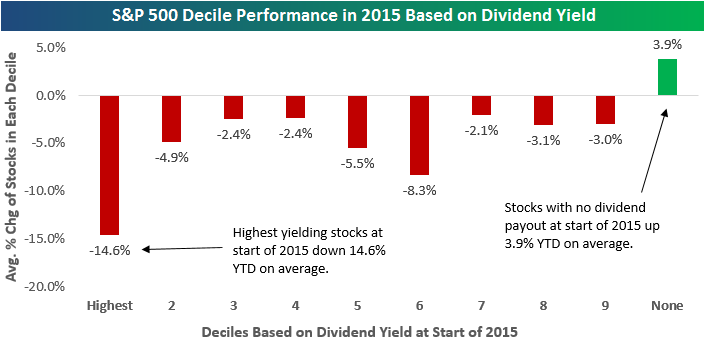

In our view, the individual stock route is the superior option for equity investing. An individual stock strategy offers the opportunity for maximum portfolio customization and allows a greater focus on companies with strong business franchises as well as long records of paying and increasing dividends.

Today, ETFs make it simple to invest in various sectors, dividend strategies, or even factor ETFs (Wall Street’s latest obsession). But in our opinion, it just isn’t practical to craft an ETF portfolio that provides exposure to our desired characteristics and risk profile without over-diversifying.

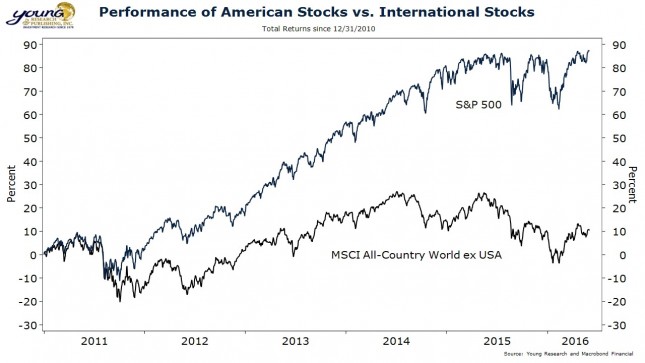

That isn’t to say that building a properly diversified common stock portfolio is easy. It can be difficult to assemble a sizable portfolio of dividend-paying stocks. First, there simply aren’t an abundance of dividend-payers to choose from. Second, when qualifiers are added into the selection process, including a focus on higher dividend-payers, the field of play is even further reduced. Third, crafting a diversified dividend-focused portfolio includes international markets and the research and time required to keep up with the global economy. Fourth, discipline is required. It can be easy to allocate too much of a portfolio to a handful of sectors or to the most recent best performers, which ultimately reduces diversification and increases risk.

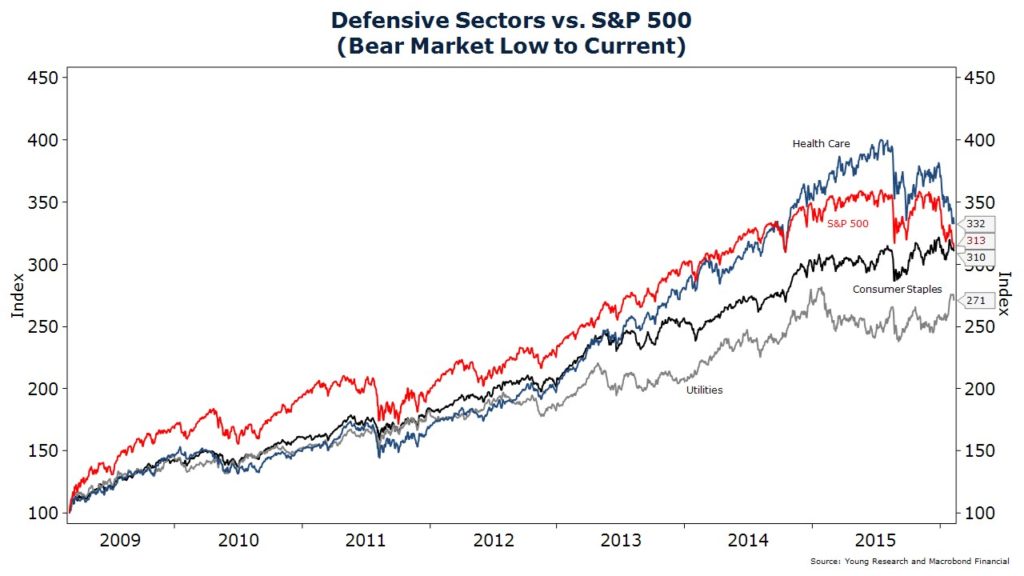

We Craft Globally Diversified, Dividend-Centric Equity Portfolios

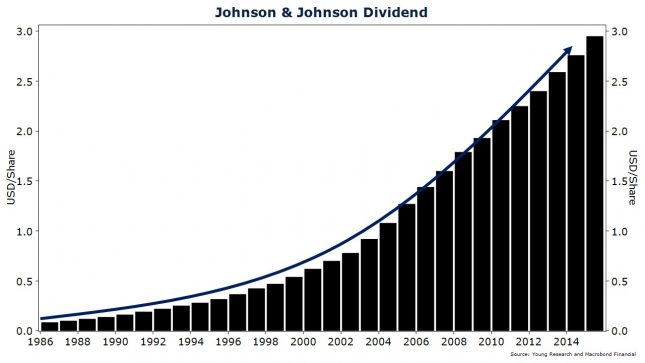

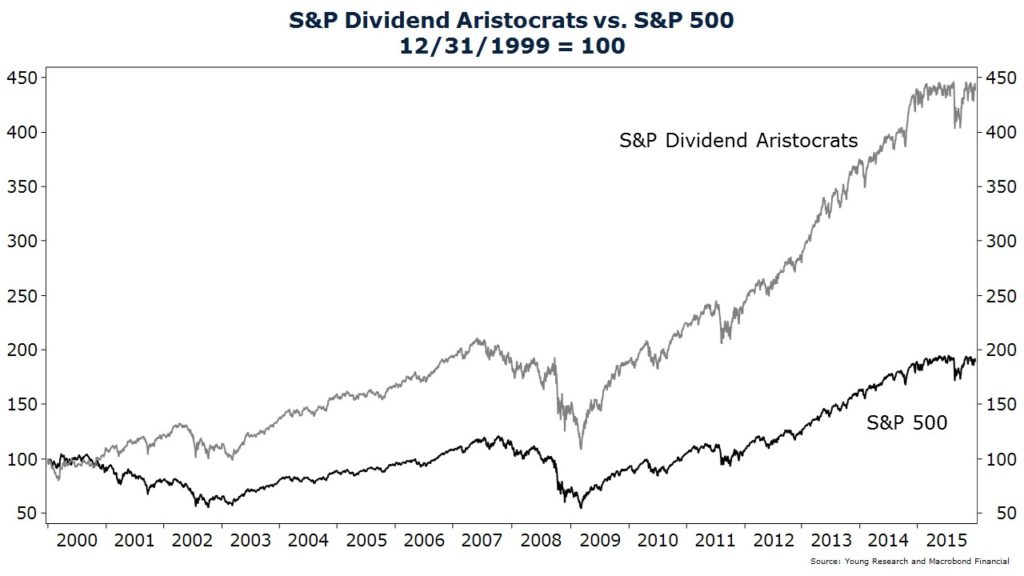

At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., we craft globally diversified, dividend-centric equity portfolios that we call the Retirement Compounders®. The Retirement Compounders® invest in companies that pay dividends and have a record of making regular annual increases. Increasingly, our focus is on companies that have increased their dividend for at least 10 consecutive years.

As Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, once said, “One of the most persuasive tests of high quality is an uninterrupted record of dividend payments for the last 20 years or more. Indeed, the defensive investor might be justified in limiting his purchases to those meeting this test.”

In addition to a strong dividend record, the Retirement Compounders® include companies’ balance sheets that appear strong and operating in industries with high barriers to entry. Companies with durable competitive advantages in the form of brand value or dominance of a unique business niche are also firms we favor.

Coming up with an approved list of stocks to buy is just the first step in our investment process. To assemble portfolios that we think offer the best risk-reward profile, we also carefully consider position sizing, sector exposure, and how each stock moves in relation to other stocks in the portfolio (counterbalancing).

Once portfolios are formed, the work of ongoing portfolio management begins. Here I am talking about the monitoring of portfolio positions, the necessary rebalancing of positions, and annual tax-loss harvesting.

A Decision to Do Nothing Is Still a Decision

Though it may be difficult to judge based on portfolio activity, the ongoing monitoring of portfolio positions is a time-intensive task. Many in the investment industry ostensibly take the view that more trading activity equates to better portfolio management, but a decision to do nothing is still a decision.

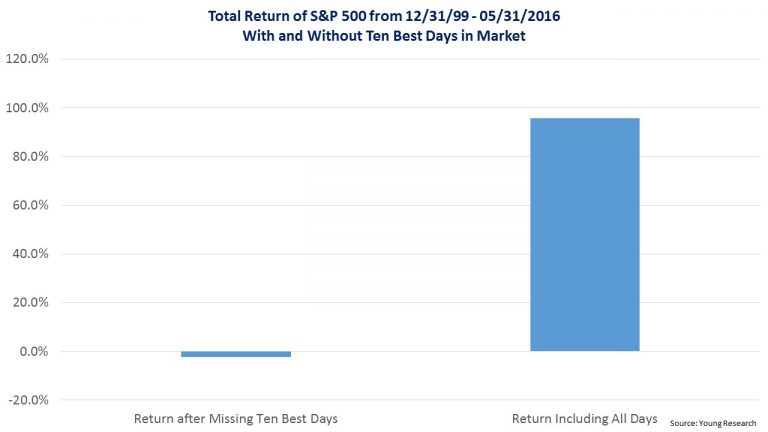

And at least speaking from personal experience, the decisions to do nothing are often the most carefully considered and tend to be the most emotionally difficult to make. Managing emotions is one of the most difficult aspects of investing for professionals as well as individuals. Emotionalism is a dangerous foe that, if not properly managed, can sabotage portfolio performance.

The investment programs we offer are designed to cater to varying risk profiles. Most portfolios are globally diversified and balanced between stocks and bonds. But we also offer an all-stock alternative for those who are both willing and able to withstand the risk and volatility of an all-equity portfolio.

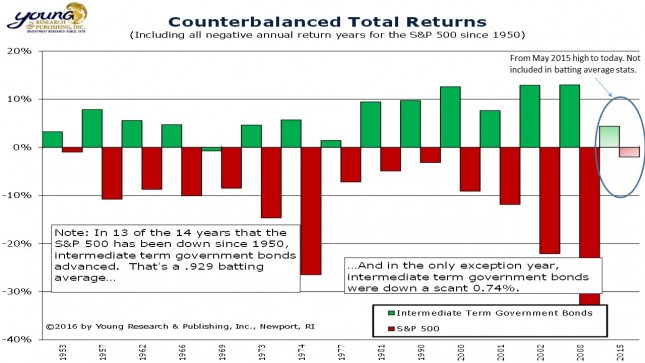

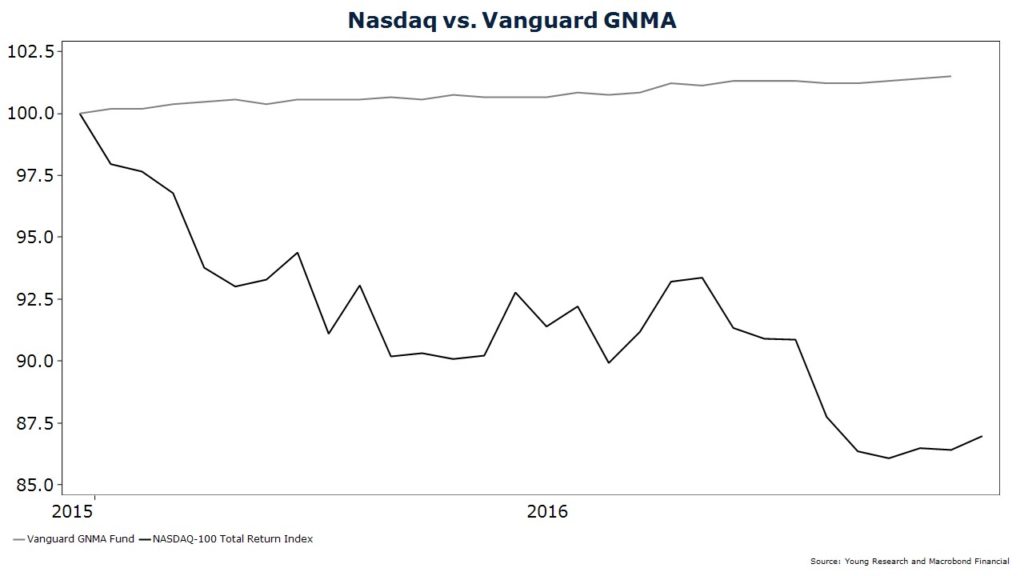

For the more conservative investor or those who simply don’t want to take on too much risk, we offer a defensive counterbalanced portfolio with a heavy weighting in high-quality bonds, a smaller allocation in dividend-paying stocks, and gold.

We first introduced gold into investment portfolios in 2005, shortly after the first physical-gold-backed ETF was listed. Our precious metals strategy is something we feel sets us apart from other investment managers. Gold can be a controversial investment in some quarters of polite society. Negative sentiment towards gold is interesting considering that up until the early 1970s the dollar was tied to gold and our own Federal Reserve still holds hundreds of billions worth of gold in its vaults.

We View Gold as an Insurance Policy

As I have written often in these strategy letters, we view gold as an insurance policy of sorts: Insurance against currency debasement, accelerated inflation, geo-political upheaval, and stock and bond market busts, among other risks.

As the earlier chart illustrates, during the two-day Brexit fallout, gold was a positive portfolio counterbalancer during a period when many asset classes were significantly down in value.

Over the years, as the investment landscape has evolved, we have added new strategies to our investment portfolios while eliminating or reducing other strategies. Gold is but one of those examples. In the early 1990s, zero-coupon Treasury bonds were a big part of our investment portfolios. The secular down-trend in interest rates acted as a tailwind to our zeros strategy. But, as the three-decade down-trend in rates started to lose momentum, the risk-reward profile of the zeros was no longer as favorable, and we started to phase out the strategy.

In the late 1990s, we had significant allocation in preferred stocks. Preferreds offered individual investors a high level of current income. As the market evolved and became dominated primarily by financial issuers, preferreds have become a much smaller part of our fixed-income portfolios. Contributing to our decision to phase out preferreds were the increased transparency and falling transactions costs in corporate bonds. Individual corporate bonds are now a major component in our fixed-income portfolios.

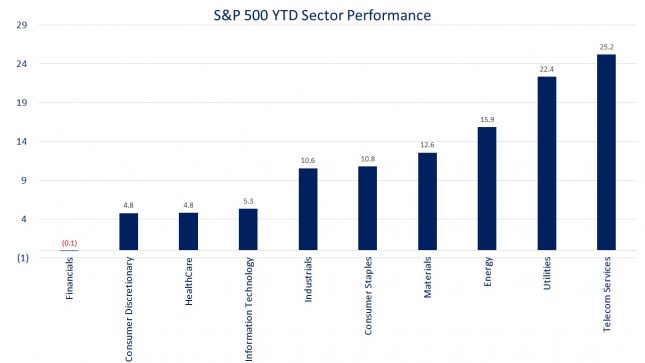

In the early 2000s we were heavily invested in REITs. REITs are still an area of interest for us, but today the reach for yield has pushed REIT valuations to levels we don’t find attractive.

More recently, we have been researching and developing a fully hedged long-short investment strategy. With the prospect of a low-interest-rate environment persisting, and investors still in need of adequate returns to fund future liabilities, the demand for returns with bond-like risk remains high. We are planning to offer a market-neutral and sector-neutral long-short portfolio. This would not replace our common stock portfolios, but would complement them. A market- and sector-neutral long-short portfolio seeks to take out stock market risk and sector risk, thereby significantly reducing volatility while still offering the prospect of modest returns (think mid-single digits). We are excited about this new strategy and are still working out the details, but will give you more information as we get closer to making the program available.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., energy MLPs have long been an industry of focus. We have viewed many of the energy MLPs as quality businesses and have, of course, favored their high yields. This month, Barron’s also made the case for MLPs.

Many investors who exited energy-focused master limited partnerships earlier this year as oil prices crashed and MLP prices fell even harder, have struggled with when—and if—to get back in. The sector rebounded sharply off its February lows, but since June, gains have stalled as investors judged the easy money had been made and risks outweighed the opportunity.

It’s time to take another look at the sector. MLPs, which yield over 7% on average, are still plenty risky and are not the stable, tax-deferred “toll takers” many investors once thought. But the biggest risks are fading, and, as third-quarter earnings season kicks off, there’s potential upside. “The tone has changed,” says Marcus McGregor, who runs MLP strategy at Conning. “Investors are more comfortable with energy and are noticing, by the way, interest rates are still low and MLP yields are attractive.”

Energy prices are not only higher, but are more stable. Crude is near $51, high enough for many U.S. producers to operate profitably, and rig counts are rising. That should lead to more oil and gas volume that needs to be transported through MLP pipes.

P.P.S. For 23 years, my mom and dad have motorcycled throughout the U.S., gathering anecdotal evidence of the state of the U.S. economy. This past spring, they retired the Harleys but continued the touring. Here are some of my dad’s observations from the past six months.

I think a lot of Americans would be shocked at how the small manufacturing sector has been hollowed out throughout New England. Sure, Boston is in stellar shape, and the area will continue to be one of the best places in America to live and conduct business. Portland is our New England sleeper. We love the whole scene in this Maine seaport. Then there are a handful of thriving bucolic outposts like the Village Green, Dorset, our favorite town in Vermont. The Dorset Inn has been our home away from home for over three decades. But beyond these and a few other exceptions, look out. On our most recent three-day swing, we toured through ultra-depressed southwestern New Hampshire, including 1929 Depression-era Fitzwilliam and Troy. Talk about dismal! One after another, formerly thriving family-operated facilities were surrounded, not by towering pines, but by tall weeds and dilapidated “For Sale” signs. The icing on the domino-disaster cake was the shuttered family diner just down the road. Sad.

P.P.P.S. Each year, Barron’s ranks the nation’s top independent advisors, and Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd. was again recognized on this list, appearing for the fifth consecutive year.

The information contained in this letter is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended nor should it be considered investment advice or a recommendation of securities. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. It is possible to lose money by investing. You should carefully consider your investment objectives and risk tolerance before investing. Please contact our office directly with any questions regarding items appearing in the letter.