The Central Bank Liquidity Bubble

June 2017 Client Letter

Many of our long-time clients may recall the name Longleaf. For those who do not, Longleaf is a family of mutual funds managed by Southeastern Asset Management. Southeastern is a boutique value manager. When mutual funds played a bigger role in our investment programs, we invested in the Longleaf funds for clients.

We’ve long considered Longleaf to be among the good guys in the mutual fund industry. The company pursues a long-term value-oriented approach that eschews the benchmark hugging and overdiversification that handicaps many mutual funds. The flagship Partners Fund is a concentrated fund that seeks to invest in 15 to 25 significantly undervalued stocks.

In early June, Longleaf announced it was closing its flagship fund to new investors. But this wasn’t your typical fund closing. Most mutual funds close to new investors because the asset base gets too large or because cash is flowing into the fund at such a rapid clip that the fund manager can’t deploy it properly. That wasn’t the case with Longleaf. Longleaf closed the Partners Fund because it saw a lack of opportunity to invest cash. In other words, the market environment for deep value investing is so bad that Longleaf can’t even find the handful of significantly undervalued companies it would take to bring the fund’s cash levels back to normal. In our view, that says something profound about current conditions in the stock market.

The Central Bank Liquidity Bubble

Why are there so few compelling deep value opportunities in the market today? Let’s start with the central banks. Global central banks, including the Fed, have held interest rates at zero for nearly a decade. Over the last ten years, trillions of dollars of liquidity have been pumped into the global financial system.

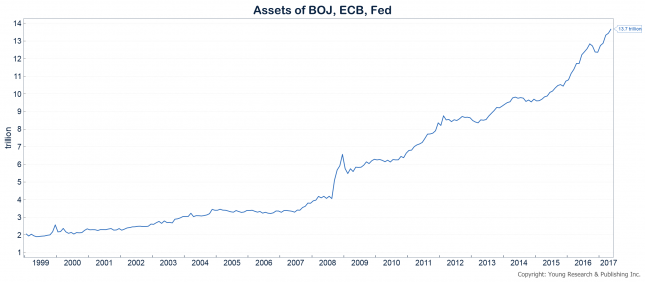

Our chart below shows the combined size of the balance sheets of the Fed, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan. These big three central banks now hold close to $14 trillion in assets, which is equal to more than 20% of the market value of all globally listed companies. And the assets continue to pile up. Even with the Fed out of the bond-buying game, the ECB and the Bank of Japan are pumping close to $2 trillion per year into the financial system.

Bubble Conditions Abound

The Fed is now raising interest rates, but the markets are saying the tightening is too late and too slow. Financial conditions, as measured by the Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index, tell the story. The Goldman index shows financial conditions that are as accommodative as they were at the point of maximum Fed stimulus in early 2015.

You can see evidence of the excess throughout the investment landscape. Cryptocurrencies including bitcoin and ethereum look like a bona fide bubble. Ethereum is up over 3,000% YTD, and the more popular bitcoin is up 150% in the last quarter alone. Argentina, a country that defaulted on its debt in 2001, then again in 2014, and six other times since its independence in 1816, just issued a 100-year bond with a yield of less than 8%.

Profitless biotech stocks have again started to soar. Young Research’s Bubble Basket, which includes Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Google, Netflix, and Tesla, is up 37% YTD. The Wall Street Journal is running front-page articles on how Amazon is going to take over America. Barron’s recently led with a feature on why the bubble conditions in the FANG stocks are set to continue. It all has the look of a “this time is different” mindset setting in.

It is rarely “different this time.”

As we see it, for the third time in the span of about 20 years, the Fed (joined this time by its brothers in arms at the ECB and BOJ) helped foster bubble conditions in financial markets. Not surprisingly Yellen & Co. deny both the existence of excesses in the markets and the Fed’s contribution to them, but the evidence should be clear.

This is Shocking

The other major factor we would argue is contributing to an absence of significantly undervalued stocks is the proliferation of value-agnostic market participants. Here I am pointing principally to index-based funds and ETFs, as well as algorithmic strategies.

J.P. Morgan recently estimated only 10% of trading volume originates from fundamental discretionary investors.

That is a truly shocking statistic.

If 90% of the volume in stocks is driven by value-agnostic investors, who are the buyers and sellers keeping a lid on valuations? The obvious implication in our view is that, with a lack of fundamental investors in the market, stocks are likely to experience much bigger booms and much bigger busts.

Goals-Based Approach Best

To avoid the emotionally draining roller coaster of a bigger boom-and-bust cycle, we believe that the mandate—now more than ever—is to pursue a goals-based approach to investing, where future liabilities (retirement income, kids’ college, charitable goals) are the priority.

In our view, investors who instead chase an arbitrary benchmark driven by a handful of the market’s most expensive stocks are more likely to make emotionally charged decisions that can sabotage performance.

How Long Will the Boom Last?

There should be no doubt in any investor’s mind that we are in the boom phase of the cycle today. But how much longer will it last? David Kostin, Goldman Sach’s Chief U.S. Equity Strategist took a stab at this question earlier this month. CNBC’s John Melloy reports:

“The unexpected mix of healthy growth and declining rates represents a Goldilocks scenario for U.S. equities,” wrote David Kostin, the firm’s chief U.S. equity strategist, in a note to end last week. “However, just like in the fairy tale, this perfect scenario is unlikely to last.”

The title of the June 9 note is “Goldilocks and the three hikes: A fairy tale scenario behind the Tech stock rally.”

Goldman believes there are two possible endings to this tale and they both aren’t great for stocks. Either the stronger growth causes the Federal Reserve to tighten more aggressively, reducing equity valuations or the current low-rate environment is “proven correct” and the pace of economic growth experiences a “significant slowdown.”

The Fed is expected to raise interest rates at the end of its two-day meeting Wednesday. The 10-year Treasury yield has gone from above 2.60 percent in March to 2.21 percent Monday.

Goldman is clearly worried the financial markets are trying to tell us something about the state of the economy. Also in the note, Kostin and his team make the point there is another rare phenomenon happening now with certain well-capitalized stocks that occurred during the dot-com bubble and may point to slowing economic growth ahead.

Investment Strategies to Navigate Bubbles and Busts

How should you position your portfolio if Kostin is right and the long boom in U.S. stocks turns into a bust?

As we regularly counsel new and existing clients to do, “Diversify.” In our view, diversification is the cornerstone of a prudent investment program. The challenge many investors have in sticking with a diversified strategy is this: When you diversify, some assets in your portfolio will probably perform poorly when others perform well.

Instinctively, many investors want to get rid of the assets going down and buy more of the assets that are going up. That would, of course, defeat the purpose of diversification.

If you have felt the urge to sell your losers simply because they are down, you are in good company. Jack Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, recently noted at a Morningstar conference that he invests about 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds, and half the time he worries why he has so much in stocks and the other half of the time he worries why he has so little in stocks.

The young man was talking about all the risks out there—global disease, pandemics, religious war, nuclear war, global warming. He said, “I don’t know what will happen. What should I do?”

“Look,” I said, “you know as much about risks coming to fruition as I do, but you should still think about your asset allocation and you don’t want to abandon stocks; you just want to get something you can live with comfortably. I’m about 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds and I spend half my time worrying about why I have so much in stocks and the other half worrying about why I have so little in stocks.”

A 50-50 stock/bond allocation is fine, probably if you’re younger a little more aggressive….

Times are different now.… The answer is not simple. I think it’s better just setting your allocation somewhere between 70-30 and 30-70, maybe averaging 50 and just hanging on. As I’ve said more than once, stay the course.

Jack’s explanation of diversification focuses on the split between different asset classes, but the same concept holds true at the individual security level as well. In a diversified portfolio of stocks, you are almost certain to hold some winners and some losers at any given time.

We Lift the Burden of Portfolio Maintenance From Your Shoulders

One service we provide to clients, to maintain proper diversification, is portfolio rebalancing. Rebalancing is one of many necessary portfolio maintenance chores that can be difficult for investors to complete. When do you rebalance? Should you change your rebalancing with the market environment? Which securities should you sell to rebalance? How far from target should you allow your portfolio to drift before rebalancing? These questions, which paralyze many do-it-yourself investors, must all be answered. The consequences of never rebalancing your portfolio can be higher risk and/or lower return. We take the burden of rebalancing off your shoulders. We answer the difficult questions and make the necessary trades to maintain the portfolio balance and risk profile that meets your indicated investment objectives.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. It has become a familiar pattern in Connecticut over the last few years. Each spring, as the state’s budget dips back into the red, legislators gather in Hartford to prognosticate over the state’s fiscal viability. They fumble around for agencies to cut, for taxes to raise, for concessions from the public unions. Eventually, they reach, with the help of Governor Dannel Malloy, some sort of stopgap deal, enough to paper over the wounds for the present fiscal year but woefully insufficient to address the roots of the longer-term problem. Connecticut is, in many ways, a state grappling constantly with the mistakes of past policy. The classic example of this pattern is the problem of unfunded pension liabilities. Among all the states in the union, Connecticut performs especially poorly in this regard: only 35.5% of its pension liabilities are funded. It’s tempting to pin the blame on current leadership, but that misses most of the story; the far more important factor is the rampant inability, or more likely unwillingness, of politicians over the last eight decades to fund the system adequately. The state has rarely if ever, contributed the requisite amount to the system and indeed contributed nothing at all for the first 30 years.

P.P.S. Amazon’s proposed acquisition of Whole Foods set the brick-and-mortar world ablaze when it was announced. Retail grocers, as well as department stores, sold off sharply on the news. Kroger, a company we follow, fell over 25%, partly on the news of the Amazon acquisition. Investors seem to be treating the news as if Amazon is going to be the only retailer and wholesaler in America that survives. While Amazon entering the brick-and-mortar space is certainly a threat to incumbents, it is also an acknowledgment by the world’s most successful online retailer that brick and mortar is far from dead. In fact, a recent Pew study found that 64% of Americans say that, all things being equal, they prefer buying from physical stores to buying online.

P.P.P.S. If you thought the last nine years of manipulation, misallocation, and mispricing that was aided and abetted by misguided monetary policy was a problem, you ain’t seen nothing yet. The Financial Times recently reported many of the world’s global central banks including the Fed are considering re-evaluating their 2% inflation targets with an eye toward raising them. The apparent theory is, if central banks can lower inflation-adjusted interest rates more than they have in the past, they will be able to provide stimulus to the economy during the next recession.

Sounds good in theory, and it probably works in the Fed’s models, but has anybody at the Fed done an honest evaluation of the last nine years of monetary policy? We’ve had nine years of the most aggressive monetary policy the world has ever seen, and all we have to show for it is bubble conditions in financial markets. Measured inflation is still below the Fed’s target, and growth has been disappointing for the entirety of the expansion. This sounds like a bad idea we hope never sees the light of day.