Is Your Bond Allocation Where It Should Be?

March 2023 Client Letter

My copy of Bogle on Mutual Funds by investment giant and founder of The Vanguard Group, John Bogle, sits on my desk as it always has during my 30 years in the investment management business. Bogle’s first chapter begins with our favorite investment strategy, compound interest. Clients know that the process of having money make money by way of reinvesting dividends and interest year after year is one way to achieve investment success.

Chapter 2 outlines another critical investment concept: risk. Bogle encourages readers to manage their investment affairs with prudence, intelligence, and discretion, and he advises them not to speculate. Further, he prompts readers to ask, “What risks are you prepared to take?”

Sitting next to my Bogle book is a copy of Benjamin Graham’s Intelligent Investor, which has been described as the best book on investing ever written. Graham, like Bogle, wastes no time on the subject of risk. The second sentence in the first chapter says, “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

Both Bogle and Graham were as concerned with not losing money as with making money. Both were also pretty good at arithmetic and understood that the greater the portfolio loss, the more challenging it is to make that money back.

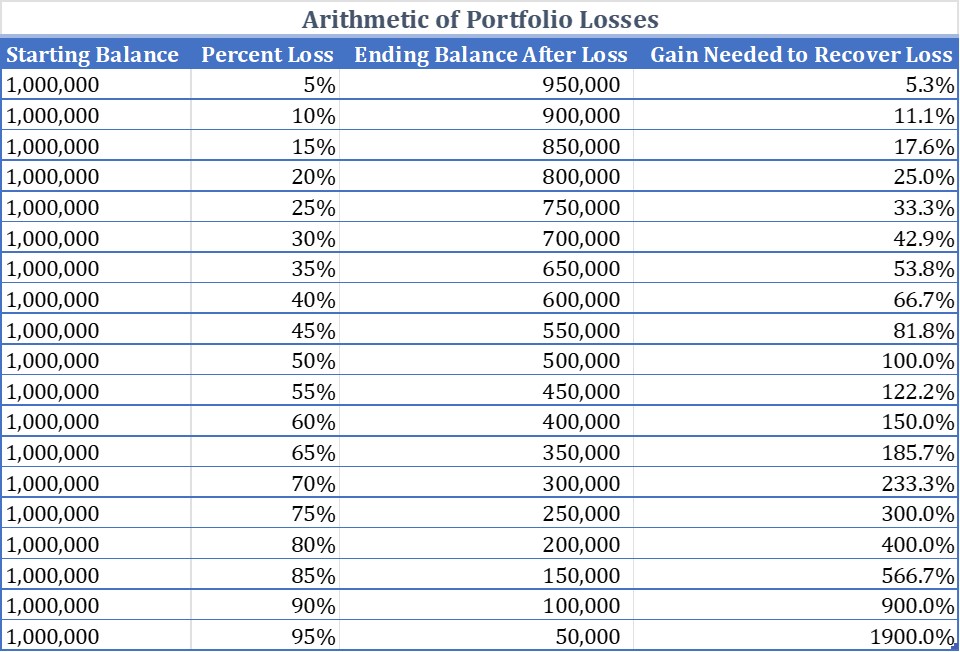

The Arithmetic of Portfolio Losses

Understanding the arithmetic of portfolio losses is vital to crafting portfolios that may help you achieve long-term investment success. All investors should know that the market can go up and it can go down. What may not be appreciated by some is the sheer magnitude of gains needed to recover from a serious loss.

Small losses are easily recouped. For example, if your portfolio loses 1%, it only takes a 1.1% gain to get back to even. If your portfolio loses 5%, it takes about a 5.25% gain to get back to even. But what if you lose 15%? Does it only take 15% to get back to even?

Unfortunately, it does not. A 15% loss in one year requires a 17.6% gain to get back to even. Not unmanageable, but as the hole gets deeper the ladder needed to climb back out gets exponentially longer. For example, the additional gain needed to recover from a 15% loss is only 2.6% more than the loss (17.6% minus 15%); but when the loss is 40%, the additional gain required to get back to even is 26.7%. In the table below, I show the gain needed to recover from a loss in five-percentage-point increments.

The typical bear-market loss in the Dow or S&P 500 is around 35%. Investors who have decided on an all-stock portfolio should be willing to accept periodic losses of that magnitude. The gain needed to recover from a 35% loss is 54%.

What if you are an investor who favors NASDAQ stocks or the high-growth innovation stocks in an ETF like ARK Innovation (ARKK)? From a high in February of 2021 to a recent low in December, the ARK Innovation ETF fell just over 80%. Investors who bought at the all-time high will require a 400% gain to get back to even.

The ugly reality of the arithmetic of portfolio losses underscores why prudence is a vital component of portfolio management. Investors with a lower tolerance for risk, shorter time horizon, or those who require annual distributions from their portfolio are often better served with a portfolio that seeks to limit downside risk rather than one swinging for the fences.

This is especially true for retired investors taking income from their portfolios. A close cousin of the arithmetic of portfolio losses is sequence of returns risk. Sequence-of-returns risk is the risk of receiving lower or negative returns early in retirement when withdrawals are being made. Of course, you don’t have to be retired to face such risk. Any investor taking regular withdrawals from their portfolio should understand how the sequence of returns can impact portfolio longevity.

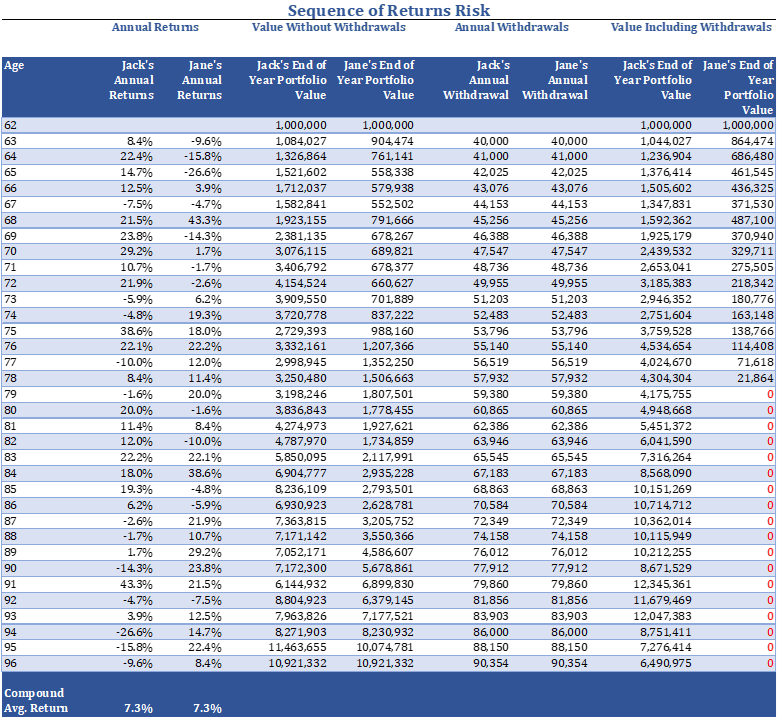

To illustrate, assume we have two investors, Jack and Jane. Feeling flush with their $1,000,000 portfolios, both decide to retire early, at age 62. (Evidently, neither investor is a client of Dick Young or Matthew Young!) Both invest their portfolios heavily in stocks. Therefore, we will assume their returns until age 96 average 7.3% per year with volatility that is commensurate with a stock-heavy portfolio.

Thus far Jack and Jane are in the same situation. They start with the same amount of money. They are investing for the same period of time and in the same type of portfolio with the same average annual return and volatility. The only difference we will make is to reverse the order of returns.

As you will recall from fourth-grade math, the commutative property says that the order of returns in a multiplication problem doesn’t matter. (Okay, I didn’t remember either, but it’s true nonetheless.) You can see in the table below by looking at the last row in the columns “Value Without Withdrawals” that the commutative property holds. Whew! At age 96, Jack and Jane both have almost $11 million despite Jane’s slow start. (As a side note, score one for compound interest. Turning $1 million to $11 million in retirement is impressive).

Now let’s assume that Jack and Jane must take income from their portfolio to help fund their early retirement. We will assume each takes $40,000 or 4% to start and they increase that draw by 2.5% per year to maintain purchasing power. The table below shows the annual income through time and their end-of-year portfolio value.

Look what happens to poor Jane. Even though Jane earns an average annual return of 7.3%, which is greater than the 4% initial withdrawal and 2.5% inflation adjustments, she still runs out of money at 79.

Jane’s withdrawals during negative return periods early in retirement permanently impair her portfolio. In stark contrast, lucky Jack’s portfolio is worth $6.5 million when he reached age 96.

Sequence-of-returns risk is a serious threat to retired investors and/or those taking portfolio distributions.

How to Reduce Sequence-of-Returns Risk

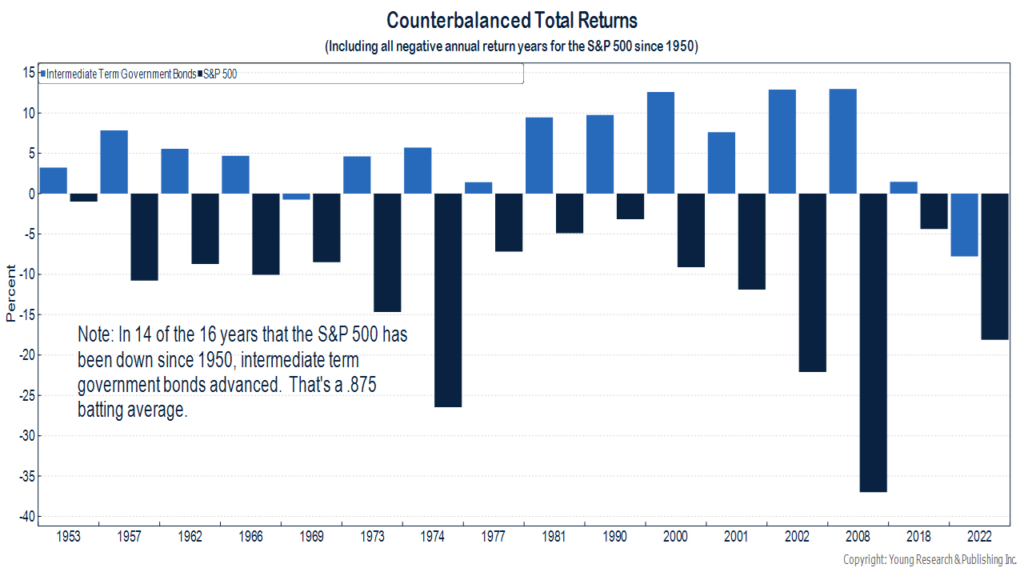

How can you reduce your sequence-of-returns risk? First, review your diversification. Spreading your assets across different sectors, industries, and especially asset classes can temper the large drawdowns that can lead to portfolio ruin when drawing income.

The most important component of your diversification should be a healthy bond allocation. If you are taking income, you have likely retired and no longer have the safety net of a regular paycheck to make up for big bear-markets. Notwithstanding last year, stocks and bonds don’t often move in lockstep. The chart below shows the performance of intermediate-term government bonds in down years for the S&P 500. Since 1950, on 14 of the 16 occasions when stocks were down, intermediate-term Treasuries were up. The dampened volatility of a balanced portfolio that includes stocks and bonds can help reduce sequence-of-returns risk.

Secondly, be sure you take a reasonable amount of income from your portfolio. What’s reasonable? It will vary based on your age and individual circumstances; but for investors starting retirement at 65, our general guidance is to stay at or below 4% and ideally shoot for something closer to 3.5%.

Finally, while nobody hopes for this outcome, if you do find yourself experiencing a big down-year in your portfolio and you have the ability to reduce your income for a year or two, do it. Giving your portfolio some time to recover can make a meaningful difference in mitigating sequence-of-returns risk.

Is Your Bond Allocation Where It Should Be?

Ensuring your bond portfolio is up to par has been challenging over the last 10 to 15 years. The Fed’s misguided policy of holding interest rates at zero and pushing longer-term bond yields lower via quantitative easing for much of this period has meant slim pickings for interest income. Today, the calculus is much more appealing.

Two years ago, short-term T-bill yields were close to zero, two-year Treasury notes paid a scant 0.20%, and if you were looking for something in the intermediate-term space like a five-year maturity, you had to settle for less than 1%. Today, even after the flight to safety bid in Treasuries from the Silicon Valley Bank failure, six-month Treasuries pay nearly 5%. Two-year Treasury notes pay you about 4.2%, and five-year notes offer a yield of 3.75%.

The power of compounding works better when there is something to compound. By example, at a 0.20% yield, it would take about 350 years to double your money. At today’s two-year Treasury note yield of 4.2%, it would take 17 years to double your money.

Implications of the Silicon Valley Bank Failure

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank has the potential to act as a catalyst for a meaningful change in the trajectory of the economy. Up to this point, the economy had responded relatively well to the Fed’s interest-rate hikes. We have seen a slowdown in the interest-sensitive sectors of the economy; but employment remains strong, and the consumer is in good shape. Core inflation, which smooths out the volatility in headline inflation, is also still running hot, which may be a sign growth is still strong. Core inflation has increased by 5.5% over the last year, with the six-month annualized rate not much better at a still elevated 5.1%. Before the SVB failure, some economists believed the Fed would need to increase rates to 6% from 4.75% today to bring inflation back down to target. We haven’t heard much about 6% Fed funds since SVB collapsed.

Its collapse not only caused a run on uninsured deposits, which is the immediate problem; but if the situation isn’t resolved quickly, we may be looking at a step-change in the availability of credit. Regulators and bank executives are likely to pursue more liquidity, more capital, and lower risk. All tend to translate into tighter credit conditions, which hampers economic growth.

It is, of course, too early to draw definitive conclusions on the economic impact of the liquidity crunch in the banking system, but its potential to be meaningful should not be discounted. While we didn’t forecast that a series of poor decisions at a modest-sized bank would catalyze a liquidity crunch in the banking system, we have been scaling back risk. As the business and credit cycles have evolved, we have ramped up most of our clients’ full-faith-and-credit-pledge Treasury holdings to 30% or more of their fixed-income holdings. We also exited bond positions rated below investment-grade in the first half of 2022. On the equities side of portfolios, we continue to hold much higher percentages of defensive shares than are represented in the broader stock-market indices.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (800) 843-7273 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. With control of Congress now split, fights over raising the debt limit will likely end up back in the headlines. If the debt limit isn’t raised, could the U.S. default on its debt? A recent op-ed in the WSJ makes clear that a U.S. default on debt would be unconstitutional:

Section 4 of the 14th Amendment is unequivocal on that point: “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law,… shall not be questioned.” This provision was adopted to ensure that the federal debts incurred to fight the Civil War couldn’t be dishonored by a Congress that included members from the former Confederate states.

The Public Debt Clause isn’t limited to Civil War debts. As the Supreme Court held in Perry v. U.S. (1935), it covers all sovereign federal debt, past, present and future. The case resulted from Congress’s decision during the Great Depression to begin paying federal bonds in currency, including those that promised payment in gold. Bondholders brought an action in the Court of Claims demanding payment in currency equal to the current gold value of the notes. The justices concluded that Congress had violated the Public Debt Clause and that its reference to “the validity of the public debt” was broad enough that it “embraces whatever concerns the integrity of the public obligations.”

That means the federal government can’t legally default. The Constitution commands that creditors be paid. If they aren’t, they can sue for relief, and the government will lose and pay up.

P.P.S. With the real estate sector slowing in recent quarters and mortgage rates more than doubling from a year ago, some are concerned about a housing market collapse. According to CNN Business, at the national level, demand for homes still outnumbers supply. “In the decade between 2012 and 2022, 15.6 million households were formed. During the same time period, 13.3 million housing units were started, and 11.9 million were completed. This includes 9.03 million single-family homes and 4.2 million multi-family homes. Of those, only 8.5 million single-family homes and 3.4 million multi-family homes are completed.”

P.P.P.S. If you have a decent amount of money stashed in a basic savings account at a major bank, there is a good chance you’re earning next to nothing on those deposits. Yes, the Fed has been steadily raising interest rates for about a year, but this has not yet translated into higher rates in bank savings accounts. According to the St. Louis Fed, savings account rates average a measly 0.35%. Fortunately, Fidelity is paying you much more in your money market account. The current rate on the Fidelity Treasury Money Market is 4.2%.

P.P.P.P.S. We recently updated both Part 2A and Part 2B of our Form ADV as part of our annual filing with the SEC. This document provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd. If you would like a free copy of the updated document, please contact us at (401) 849-2137 or email cstack@younginvestments.com. Since the document was last updated in March 2022 there have been no material changes.