Market Corrections are Normal

August 2015 Client Letter

In August, a five-day financial markets rout saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, and the Nasdaq each decline over 10%, serving as a reminder that markets do indeed go down. The negative backdrop to the five-day mini-crash was evidently initiated by worries over China’s slowing economy, currency devaluation, and a drop-off in commodity prices.

On the heels of this volatility, it is important to remember that market corrections are normal. Investors have enjoyed a relatively long period with minimal volatility. It’s been almost four years since the S&P 500 experienced a 10% correction. Generally speaking, though, long stretches without market declines are not normal. On average, investors can expect three 5% corrections per year, one 10% correction per year, and one bear market (20% or greater decline) every three years. The last four-year period has been far from average.

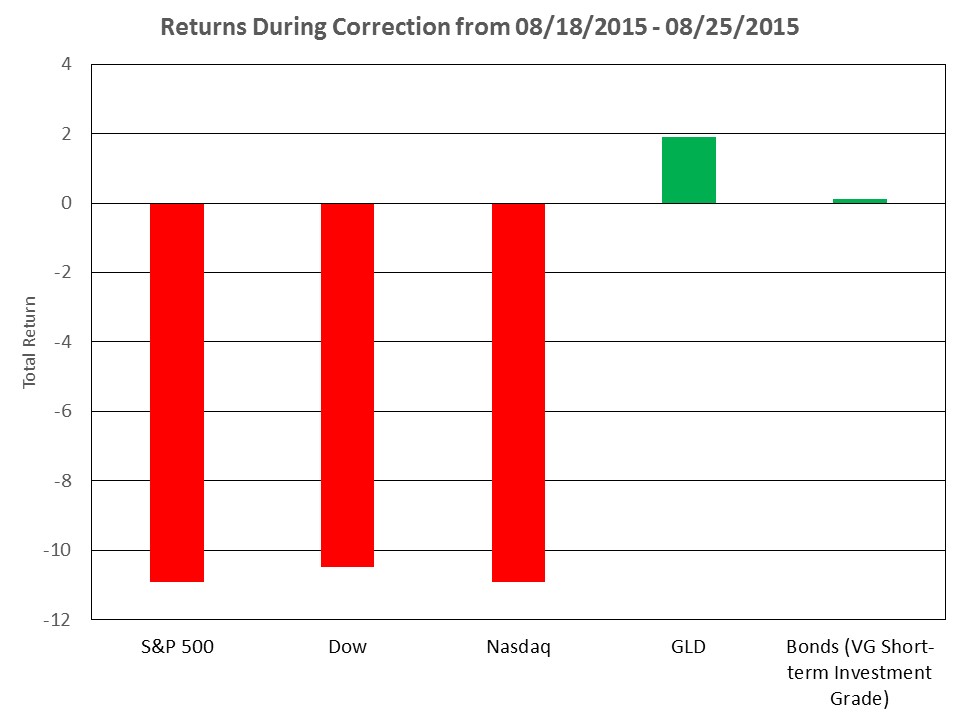

However, while some volatility is normal, it was still somewhat jarring to witness how quickly the market took on losses. Fortunately, most clients of Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd. own portfolios containing a balance of different asset classes. Over longer periods of time, a balanced portfolio is usually a good idea. It’s not that balanced portfolios offer the highest returns—historically, an all-stock portfolio would have higher returns over long time periods. Rather, balanced portfolios tend to work well because investors find it easier to ride out corrections with a mix of asset classes. A diversified portfolio can help avoid regrets when part of the financial markets take a plunge. By example, the chart below illustrates how stocks, bonds, and gold performed during the recent correction.

Jack Bogle, the founder of the Vanguard Group, who has about as much experience as anyone in helping individual investors ride out volatility, had this to say to The Wall Street Journal in December 2007:

I think a very important lesson is: Don’t let your emotions drive your investment program, because you will be thinking of getting in and out. For investors the best rule by and large is to ignore the daily moves of the stock market. The stock market is a giant distraction for the business of investing. Buy and hold a very diversified portfolio, U.S. and global….Another important lesson: Always hold some bonds.

The markets’ August sell-off was likely fueled by the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing, which resulted in an abnormally low interest rate environment. As the Fed purchased large amounts of long-term bonds and promised to hold short-term rates near zero, investors eschewed bond purchases and instead hopped on the equity bandwagon.

As my dad recently wrote in regards to the Fed:

The Fed, through the long business recovery that commenced in 2009, has mistakenly sat on its hands—an action thoroughly without precedent. Based on the clear lessons of history, we should have seen a stair-step pattern of interest rate increases years ago. Rather than allowing Wall Street to reap what it sowed, the government—along with its privately owned (yup) cousin at the Fed—determined it would let retirees, hunkered down in their retirement condos in Boca, pick up the tab for Wall Street’s recovery. This was achieved by holding short-term interest rates at near zero, allowing Wall Street to speculate and recover for years at next to nothing.

When the current economic cycle turns, there may be a more limited scope for a policy response than in past cycles. Government debt relative to the economy is greater than in the past, the Fed has a $4-trillion balance sheet (as opposed to under $1 trillion before the financial crisis), and interest rates are already pegged near zero. If the economy unravels, the stock market could experience a significant correction. We would expect the NASDAQ-oriented universe to get hit the hardest in such a scenario. The strategy we advise in light of such a risk is to favor higher-quality companies offering a more predictable cash flow and a strong likelihood of being able to ride through a down cycle.

With our common stock investment strategy, we craft portfolios generating a steady stream of dividends. We have long favored stocks with above-average dividend yields, a history of paying dividends, and a history of annual dividend increases. More recently, we have started putting less emphasis on initial yield and greater emphasis on companies that have increased their dividend for at least 10 consecutive years.

With the Federal Reserve pinning interest at zero for an unprecedented six years into an economic recovery, we are seeing yield-reaching galore in some sectors we have long favored. Dividend yields are now lower, and valuation risk is higher.

Electric Utilities and the Reach for Yield

One sector we believe has been impacted by the reach for yield is the electric utilities industry. For years, electric utilities have been a foundational holding in our stock portfolios. Today, yields are low, and dividend growth rates have been pared down. Volatility has also picked up as investors rush in and out of the sector at every hint of a change in interest rates. Long term, the industry may also face headwinds from solar. Large customers could start generating some portion of their own electricity from solar or pulling off the grid entirely. As a result, a much smaller percentage of the utilities industry now qualifies for consideration in our portfolios. We don’t feel it is urgent to make a wholesale exit from our electric utility holdings, but we are using certain positions as a source of funds to buy companies with a 10-year record of dividend increases.

Two recent additions we’ve made to portfolios that have increased their dividends for at least 10 consecutive years are Harris Corp. and Target.

Harris Corp. is an international communications equipment company. Standard & Poor’s classifies Harris in the information technology industry—the same sector as the likes of Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo!, and Apple. But Harris isn’t your typical flash-in-the pan technology company like those we have long avoided.

In the 1890s, Alfred and Charles Harris owned a jewelry store in Niles, Ohio, where they would tinker with new technologies in their free time. Their first major success was the invention of a sheet-feeding system that fed paper into printing presses automatically. The system’s capabilities were so advanced that the brothers understated them in order to seem more believable to potential customers.

Like many turn-of-the-century industrial technology companies, Harris Corp. would eventually begin to broaden its horizons. One of its pivotal acquisitions was Radiation Inc., which in 1967 brought Harris Corp. into the business of manufacturing equipment for the fledgling space industry and the military.

Today, Harris is a leading communications firm serving the military, the government, and major corporations.

There are six “core franchises” at Harris Corp. These are businesses that get the most attention and the most revenue. They include space and intelligence, air traffic management, weather, electronic warfare and avionics, tactical communications, and geospatial systems. Harris is building the critical advanced technology running the government’s most important systems.

Harris Corp. has increased its dividend for 13 consecutive years. Over the last 10 years, the dividend has increased at a compounded annual rate of 23%.

Like Harris, Target has a long and successful history. Target began when George Draper Dayton purchased land in Minneapolis on Nicollet Avenue in 1881. There he formed the Dayton Dry Goods Company, which would eventually become Target. Dayton was a philanthropist and business pioneer who wowed America with his determination and creativity. In 1920, he used two Curtiss Northwest Airplane Company planes to haul goods from New York to Minneapolis after railroad strikes shut down overland transport. At the time, the trips were the longest commercial flights ever.

Today, Target operates 1,934 stores in the U.S. and Canada and employs 366,000 people. Target is ranked 22nd on Fortune’s list of the world’s most admired companies. In 2013, Target produced revenues of $72.6 billion, of which 25% represented household essentials, 21% food and pet supplies, 19% apparel and accessories, 18% hardlines (things like hardware, automotive parts and accessories, sporting goods, electronics, toys, etc.), and 17% home furnishings and decor. Target has paid dividends every year since 1965.

Target is operating with an eye toward the future. Currently, the grocery business at Target generates only 20% of its sales. Target hopes to attract more repeat customers by bulking up its grocery offerings. By adding just one more visit per customer each month, Target will generate an additional $2.5 billion in sales each year.

Target has increased its annual dividend for 43 consecutive years. The company’s 10-year dividend growth rate is 20%. Today, Target shares offer an above-average yield of 2.8%.

By crafting a portfolio of dividend increasers such as Harris and Target, we believe there is less need to be concerned with interim portfolio values and stock prices. Instead of focusing on minute-by-minute, day-by-day, or quarter-by-quarter performance, think of yourself as a collector of dividends. As long as you have received more dividends this year than last, you can consider yourself to be winning the war.

Have a good month and, as always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Sincerely,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. From John Tamny, “The Housing Lesson within the Ugly Plunge in Apple Shares,” Forbes, August 9, 2015:

Back in the late 1990s, and amid a rather glorious bull market, Goldman Sachs partner David Henle preached calm to clients and employees alike. To paraphrase Henle ever so slightly, “View your equity holdings in the same way you do your house. You don’t check your house’s value on a daily basis, nor should you regularly check the value of your equities. Since you’ll own both for the long-term, near-term volatility shouldn’t concern you.”

P.P.S. From Stephen Roach, “Market Manipulation Goes Global,” Project Syndicate, July 27, 2015:

Market manipulation has become standard operating procedure in policy circles around the world. All eyes are now on China’s attempts to cope with the collapse of a major equity bubble. But the efforts of Chinese authorities are hardly unique. The leading economies of the West are doing pretty much the same thing—just dressing up their manipulation in different clothes.

Take quantitative easing, first used in Japan in the early 2000s, then in the United States after 2008, then in Japan again beginning in 2013, and now in Europe. In all of these cases, QE essentially has been an aggressive effort to manipulate asset prices. It works primarily through direct central-bank purchases of long-dated sovereign securities, thereby reducing long-term interest rates, which, in turn, makes equities more attractive.

Whether the QE strain of market manipulation has accomplished its objective—to provide stimulus to crisis-torn, asset-dependent economies—is debatable: Current recoveries in the developed world, after all, have been unusually anemic. But that has not stopped the authorities from trying.

P.P.P.S. From Jeff Sommer, “The High Cost of Investing Like a Daredevil,” The New York Times, June 6, 2015:

“When investors think short-term and try to time the market, they haven’t done very well,” Louis S. Harvey, the president of Dalbar, a Boston research firm, said in an interview. “They have been leaving a lot of money on the table.”

. . . By buying and selling too frequently and at the wrong times and not benefiting fully from compounding, people typically do even worse than they would have done if they simply held on to their investments—even if those investments were in mutual funds that themselves trailed the market, Dalbar found. In short, investors have been penalized multiple times—for buying funds that underperform, for selling those funds at the wrong times and, often, by generating unnecessary costs by trading relatively frequently.”