Problems with the World’s 4 Biggest Economies

September 2011 Client Letter

Over recent years, we have advocated and pursued what we consider to be a defensive investment strategy. Our caution has centered on the troubling condition of the global economy. Today, the world’s largest economic players face powerful structural headwinds likely to constrain economic growth. Yet many economists, policymakers, and investors have operated with an optimistic outlook. We contend that problems exist and that many financial assets are not reflecting this reality.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the world’s four largest economies, in order of size, are the United States, the euro area, China, and Japan. In aggregate, these four countries generate almost 60% of the $69 trillion in global GDP. Most agree that without strong fundamentals in the “Big 4,” global economic growth will remain slow. Unfortunately, the fundamentals of the Big 4 are on shaky ground. I want to briefly describe some of the headwinds facing the world’s four largest economies.

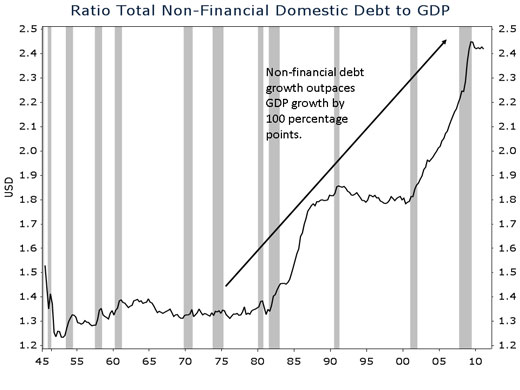

The U.S. is riddled with problems, but debt is the nation’s biggest challenge. Over the last three decades, American households, businesses, and government borrowed too much. Debt growth outpaced economic growth by more than 100 percentage points. But debt can only grow faster than income for so long. There are limits to the amount of leverage a business, an individual, or a nation can service. In our view, the American economy has reached that limit. Deleveraging is now necessary.

Though you wouldn’t know it from looking at our debt-to-GDP chart above, the private sector has already started to deleverage. Household debt has fallen to .88X GDP from .98X GDP in 2009—the largest decline since records began over 50 years ago.

But if the private sector is deleveraging, why hasn’t total debt-to-GDP ratio fallen? Enter Washington.

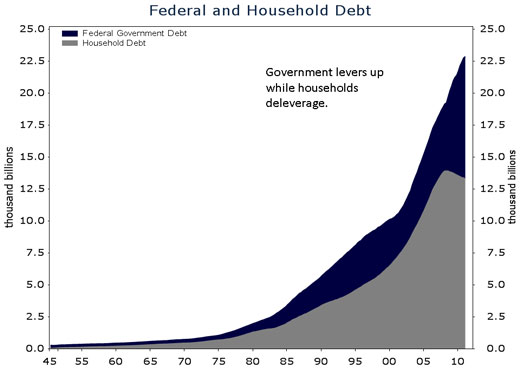

Take a look at our next chart. Here we show the total amount of household and federal government debt. The drop in household debt has been more than offset by an increase in government debt. Policymakers have been reluctant to allow the economy to deleverage. But supplementing private-sector spending and borrowing with government debt and deficits only delays the inevitable. The status quo isn’t sustainable. The U.S. is borrowing almost 40 cents of every dollar it spends. On a $3.8 trillion budget, that adds about $1.5 trillion to the debt each year.

To prevent a debt crisis in coming decades, the federal government needs to reduce the national debt. However, if large reductions occur, it is important to understand that austerity is bearish for growth (and the stock market) in the short run. Government spending and borrowing are artificially keeping the economy stronger than it otherwise would be. If the U.S. balanced its budget tomorrow, more than $1 trillion in spending would be taken out of a $15-trillion economy.

So the global economy’s lead horse is on the verge of a deleveraging process that is likely to hold back economic growth in the medium term. The world’s second-largest economy is the euro area. As you may know, the euro area is neck deep in a sovereign debt crisis. Greece has been given lifeline after lifeline because, like policymakers in the U.S., euro-area policymakers are reluctant to accept the inevitable.

Even after a modest restructuring plan that was recently approved by euro-area policymakers, Greece has too much debt. A default appears to be the only long-term solution in sight today. The same may be true of the euro area’s other peripheral economies. The E.U. is advising austerity for overly indebted euro-area nations, but austerity isn’t working.

In 2011, the Greek and Portuguese economies are expected to contract by 3% and 1.5%, respectively, while economic growth in Ireland and Spain won’t break 1%. Lower economic growth raises the debt burden.

The euro area’s problem is not so much overly indebted members as it is a structural flaw in the currency union’s design. Euro-area economies are a diverse bunch. There are mature economies such as Germany that average growth of less than 2% and emerging economies such as Estonia that average growth in excess of 5%. When policymakers apply the same monetary policy to vastly different economies, imbalances result.

If the euro is to avoid a breakup, we see only one option that would permanently resolve the instability that is plaguing the region—tighter integration. A fiscal union or political union in conjunction with labor-market reforms and greater labor mobility would increase the stability of the euro area and the viability of the common currency. The problem with greater integration is that the polls show the public set against it. Citizens don’t want to give up their sovereignty. The frugal Finns don’t want to bail out the profligate Greeks, and more importantly, the Germans want no part of a fiscal union or anything like it. In Germany, a majority of the public thinks the original rescue of Greece was a mistake. And 60% reject offering further assistance.

That doesn’t bode well for the future of the euro, or economic growth in the region. The threat of sovereign default or a euro breakup is likely to weigh on euro-area growth until the matter is permanently resolved.

If the U.S. and the euro area aren’t going to lead the global economy, can China save us? China is, after all, the world’s fastest-growing large nation. We don’t have high hopes for such a scenario. It is true that China’s economy may contribute to global growth, but if you’re looking for a structurally sound economy, China is not it. China’s economy has serious structural flaws—which we believe are more severe than those in the U.S. or the euro area.

Though it is not often mentioned by China bulls, it is important to remember that China is still a command-style economy. Command economies have a long history of failure. The most common shortcoming of command economies is their propensity to misallocate resources. China is no exception. The Communist Party’s management of the Chinese economy has resulted in massive misallocation of capital in the country. An intentionally undervalued currency, poor incentives for political leaders, and a government-controlled banking system are all to blame. There is a property and fixed-asset investment bubble that, according to one formerly bullish China expert, could produce a “major, major economic correction.” Investment bank Standard Chartered estimates that about 50% of China’s GDP is linked to the fate of its real-estate market. That’s a scary thought, especially since Chinese policymakers have been tightening monetary policy in an effort to slow inflation. A hard landing could be in store for China. And if it is, investors crafting portfolios on the hope that China will drive global economic growth are in for an unpleasant surprise.

That leaves Japan. With GDP of $5 trillion, Japan is the world’s fourth-largest economy. Is Japan any more structurally sound than the U.S., euro area, or China? Do two lost decades of economic growth, persistent deflation, a declining population, and a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 200% seem structurally sound to you? Japan’s excessive government debt is a disaster waiting to happen. The country has managed to avoid financial collapse up to this point because it has been able to finance itself with private-sector savings at sub-2% interest rates. But Japan’s population is aging, and as it ages, the country’s savings rate falls. By 2015, the household savings rate is expected to dip into negative territory. If Japan can’t finance itself domestically, external creditors will have to close the gap. What’s the problem with Japan turning to external creditors? The problem is the rate of interest. At today’s sub-2% borrowing rates, debt service eats up 20% of government revenues. If external creditors demand a yield more on par with yields on U.S. and euro-area bonds, Japan’s debt service costs could consume the country’s budget.

All in all, it is a pretty bleak picture for the global economy. The world’s four largest economies, accounting for almost 60% of GDP, face major structural headwinds that are likely to weigh on growth in the medium term. And without vibrant growth in the “Big 4,” global economic growth is likely to muddle along at a lackluster pace.

Until the structural headwinds subside or financial markets start pricing in the challenged outlook for the global economy (the latter is starting to happen), we will maintain our defensive approach.

Our defensive approach relies on several tactics. First, we focus on cash-generating securities. A predictable stream of interest and dividend payments not only can supplement spending needs but also provides a sense of comfort that appreciating markets are not the only fuel for portfolio growth. Second, we primarily invest in bonds and stocks of companies we believe to be higher quality. High-quality companies tend to stay in business and tend to continually make timely interest and dividends payouts.

Third, while we believe in a diversified portfolio, we do not wish to over-diversify. Long bonds, technology shares, and much of euro land are currently not welcome in a Young portfolio. Instead, we include favorites like short-term corporate bonds, utilities, consumer staples, pipelines, Canada, and Switzerland.

Have a good month, and as always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Sincerely,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. The Fed’s August decision to hold interest rates near zero for another two years has pushed short-term Treasury rates of varying maturities down to levels near zero. The five-year Treasury now yields less than 0.95%. We are adapting our fixed-income strategy to the current environment to enhance portfolio yield. We plan to rely more heavily on a roll-down strategy and high-yield bonds, which have become more attractive in the recent market sell-off. I’ll describe each strategy in more detail next month.

P.P.S. Most investors understand the concept of total return. Total return is calculated according to the following formula: capital gains + dividend yield = total return.

Total return could also include a third element, dividend growth. When you have dividend growth, your investment has a better chance to keep pace with inflation.Our Retirement Compounders equity portfolio invests in 32 dividend-paying securities, and a majority of the securities increase their dividend annually. Today, our Retirement Compounders program has a current yield around 5%.

P.P.P.S. As recently noted in SmartMoney magazine, a regular check isn’t the only way that a dividend-paying stock can benefit retirees.

Recent research by Michael Goldstein, finance professor at Babson College, shows that dividend stocks as a group outperform nonpayers over time, in both up and down markets. Goldstein points out that dividend-paying companies tend to be more financially sound, which may account for the outperformance.