The Sweden Solution to Weak Growth

September 2012 Client Letter

Few would accuse Sweden of being a free-market utopia. Not with a top marginal rate of 57% for personal income tax and government spending equal to 56% of GDP. However, during the last two decades, Sweden cut its public debt to 33% of GDP from a high of nearly 80%. Last year, Sweden eliminated its deficit. And for good measure, the Prime Minister, Fredrik Reinfeldt, recently announced his intention to cut the corporate tax rate from 26.3% to 22% (The U.S. corporate tax rate is 35%).

When announcing the proposed cuts, Mr. Reinfeldt labeled the corporate income tax as “probably the most harmful tax of all,” because of its negative impact on job creation and business investment. Corporate taxes can lead to double taxation when profits are taxed at the corporate level and taxed again when they are distributed as dividends.

Today, Sweden is in a strong fiscal position in part because the country side stepped the worst of the 2008 financial panic and avoided the Keynesian policies practiced by many other countries. Sweden’s conservative finance minister, Anders Borg, responded to the 2008 financial crisis with a permanent tax cut to speed recovery. In general, Borg aims to reward work by cutting income-tax rates, pushing retired people back into the labor market by reducing some government benefits, and promoting productivity by increasing competition.

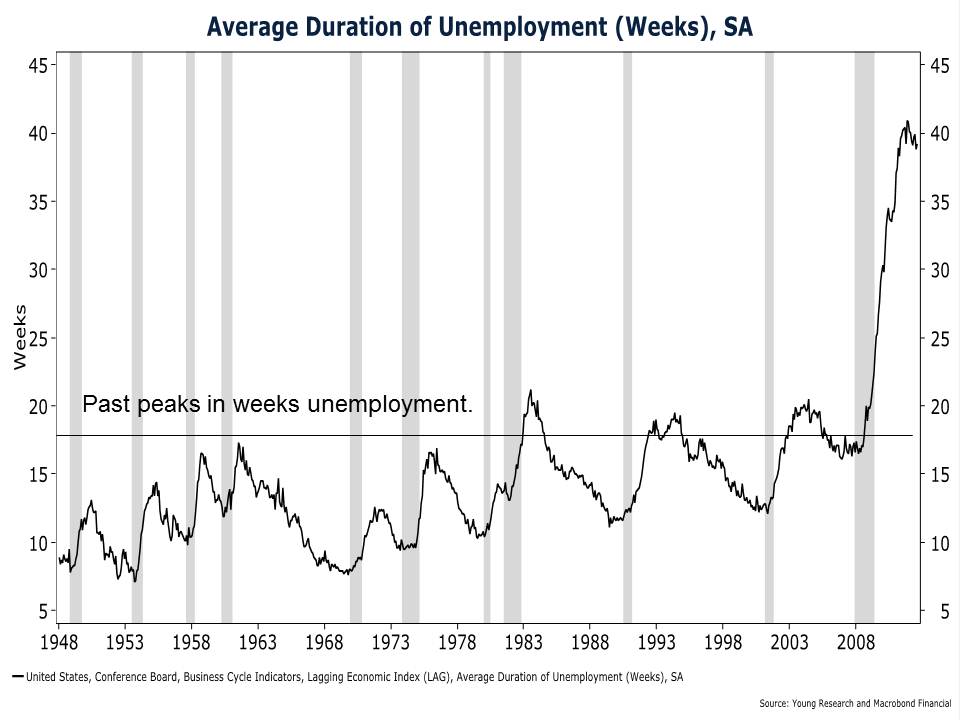

The U.S. could certainly use a dose of Borg economics. Weeks of unemployment is a solid measure of the health of the economy and structural employment. Our chart gives you a bird’s-eye look all the way back to 1948—that’s a lot of history.

Today, shockingly, you can see Americans are unemployed at twice the historical norm in terms of number of weeks unemployed. We have never witnessed as ugly an employment scene as we have today. The current administration favors a strategy of income redistribution through higher taxes. Such a strategy should concern everyone, especially those who are retired and soon to be retired.

Another concerning strategy, and one most likely not in the Borg playbook, is the one currently being implemented by Ben S. Bernanke. At its last policy meeting, the Fed announced it would restart the printing press at a rate of $40 billion per month. The newly printed money will be invested in mortgage-backed securities (since the Fed has already nationalized most of the Treasury market). Including the extension of Operation Twist, the Fed will buy $85 billion per month in long-term securities. The Fed also announced it will hold interest rates at zero until at least mid-2015.

So even though QE II, 0% interest rates, a commitment to hold rates at 0% for what seems like forever, Operation Twist I, and Operation Twist II have had almost no discernible impact on the real economy, Bernanke is doing more—in fact, he is going all in. This time, there is no end in sight to the money printing. The Fed is going to keep the printing presses rolling until the labor market improves “substantially.” And if it doesn’t, guess what? Bernanke promises to print even more money.

What is the justification for more monetary activism? The stock market is bordering on a post-crisis high, short- and long-term interest rates are at record lows, the housing market is improving, inflation is at the Fed’s target, and economic growth, while it should be better, isn’t cratering. Those don’t sound like conditions that warrant emergency monetary policy. How is more liquidity going to help the labor market?

Evidently, Mr. Bernanke hasn’t given up on the Fed’s asset-bubble approach to monetary policy. At the press conference following the Fed’s last meeting, when Bernanke was asked how an unbounded money-printing campaign would actually help economic growth, he answered:

To the extent that home prices begin to rise, consumers will feel wealthier, they’ll feel more disposed to spend. If house prices are rising, people may be more willing to buy homes because they think that they’ll, you know, make a better return on that purchase. So house prices is one vehicle. Stock prices, many people own stocks directly or indirectly. The issue here is whether or not improving asset prices generally will make people more willing to spend. One of the main concerns that firms have is there is not enough demand, there’s not enough people coming and demanding their products. And if people feel that their financial situation is better because their 401(k) looks better for whatever reason, their house is worth more, they are more willing to go out and spend and that’s going to provide the demand that firms need in order to be willing to hire and to invest.

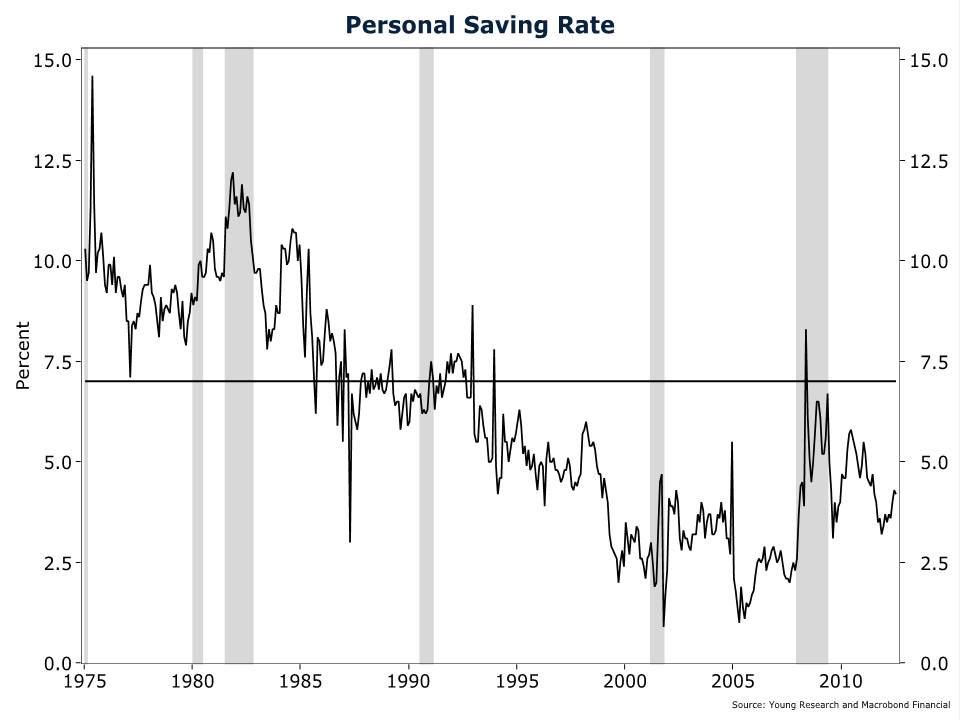

In other words, the Fed plans to artificially prop up asset prices to encourage consumers to spend money. Money they don’t have. Check out our chart on the personal savings rate. Consumers are only saving 4% of their income, compared to a long-run average of 7%. Using illusory gains in wealth to fool Americans into spending is the same strategy that resulted in two asset bubbles and the worst recession since the Great Depression.

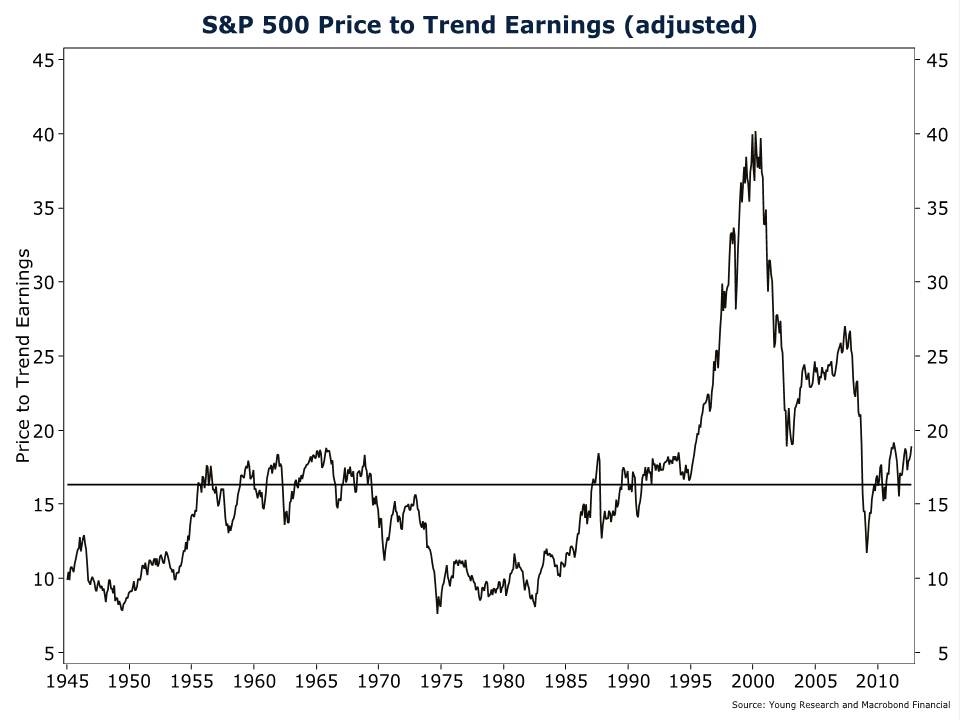

What’s more is a third round of money printing may not even boost asset prices as the Fed desires. As I mentioned earlier, the stock market is already bordering on a post-crisis high. In relation to normalized profits, stocks are far from cheap (see chart on price-to-trend earnings). And with revenue and earnings growth slowing sharply, investors may be reluctant to bid up stock prices much further.

The Bernanke Fed long ago lost its bearings on the role and purpose of monetary policy. An unbounded money-printing campaign is going to push the economy deeper into the easy-money abyss. This isn’t just the opinion of Young; even the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the central bank for central banks, has warned of the consequences of the continued use of emergency monetary accommodation. From the latest BIS annual report (emphasis is mine):

any positive effects of such central bank efforts may be shrinking, whereas the negative side effects may be growing. Both conventionally and unconventionally accommodative monetary policies are palliatives and have their limits. It would be a mistake to think that central bankers can use their balance sheets to solve every economic and financial problem: they cannot induce deleveraging, they cannot correct sectoral imbalances, and they cannot address solvency problems. In fact, near zero policy rates, combined with abundant and nearly unconditional liquidity support, weaken incentives for the private sector to repair balance sheets and for fiscal authorities to limit their borrowing requirements. They distort the financial system and in turn place added burdens on supervisors.

With nominal interest rates staying as low as they can go and central bank balance sheets continuing to expand, risks are surely building up. To a large extent they are the risks of unintended consequences, and they must be anticipated and managed. These consequences could include the wasteful support of effectively insolvent borrowers and banks—a phenomenon that haunted Japan in the 1990s—and artificially inflated asset prices that generate risks to financial stability down the road. One message of the crisis was that central banks could do much to avert a collapse. An even more important lesson is that underlying structural problems must be corrected during the recovery or we risk creating conditions that will lead rapidly to the next crisis.

In addition, central banks face the risk that, once the time comes to tighten monetary policy, the sheer size and scale of their unconventional measures will prevent a timely exit from monetary stimulus, thereby jeopardising price stability. The result would be a decisive loss of central bank credibility and possibly even independence.

The potential for a disorderly exit from the Fed’s inflated balance sheet is especially worrying. Never in its history has the Fed injected so much high-powered money into the financial system. Bernanke & Co. have zero experience exiting unconventional monetary policy. Will the Fed be able to successfully wind down its balance sheet without first letting the inflation genie out of the bottle or causing another recession? Mr. Bernanke assures us he is 100% confident the Fed can control inflation. But the Fed is always under immense political pressure to keep the easy-money party going. If inflation starts to accelerate while unemployment remains elevated, will Bernanke (or a future Fed chairman) actually tighten policy and risk higher unemployment? And even if he does tighten policy before inflation accelerates, will he go too far and push the economy back into recession?

The Fed doesn’t exactly have a stellar record in managing the economy. It often keeps rates too low for too long during easing cycles and raises rates too high during tightening cycles. The sobering reality is since January of 1971, there have been eight Fed tightening cycles and six recessions. All six recessions came on the heels of Fed tightening cycles. And that was with standard monetary policy. The odds may be worse when exiting unconventional policy. At the very least, the historical record points to a 75% chance the Fed will push the U.S. back into recession when it tightens monetary policy.

In our view the short-term stock-market gains from the Fed’s latest money-printing campaign are likely to prove illusory. The Fed is pulling demand and asset price returns forward. The cost is likely to come in the form of weaker future growth, lower investment returns, and higher future inflation and interest rates.

How do you preserve and protect capital in an unbounded money-printing world? We continue to advise a defensive approach. While monetary accommodation may temporarily unmoor prices and fundamentals, history shows such a divergence is usually resolved in favor of the fundamentals.

In fixed income, we continue to keep maturities short to guard against a rise in inflation and interest rates. We are adding yield to fixed-income portfolios by favoring credit risk as opposed to maturity risk. We own gold, silver, and foreign currencies to hedge against the heightened risk of currency debasement. And in equities, we favor a globally diversified portfolio of high-dividend-paying stocks with a history of dividend increases. We focus on companies with strong balance sheets and high barriers to entry—those companies we believe are most equipped to thrive in any economic climate.

Have a good month, and as always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Sincerely,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. Here is a common pitch you may have heard from the perma-bull crowd. Stocks are cheap relative to bonds. The earnings yield on stocks far exceeds the yield on Treasury bonds. Is this a reason to be bullish on stocks? There are many issues with this line of thinking, but just for starters, here are two problems. First, stocks and bonds are different assets. Stocks are risky; bonds are much less risky. Thus, stocks should always be priced to deliver higher returns than bonds. Second, this is a relative-valuation argument. What if bonds are overvalued as they are today? A good guide to a fair yield on Treasury bonds is the growth rate in nominal GDP. Nominal GDP is growing at about 4%. Ten-year Treasuries yield about 1.8%, so bonds are deeply overvalued. If bond yields rise to 4%, do stocks suddenly become overvalued? Justifying the purchase of stocks based on bond yields is lazy analysis. Stocks should be valued on their own merits.

P.P.S. The states are the nation’s laboratories of innovation. Some state governments have worked hard to address the problems facing their citizens. Others have created boneheaded programs that will do little to solve the problems facing their constituencies. One of the smarter reforms in state government during this year has been the education overhaul in Louisiana shepherded by Governor Bobby Jindal. The reforms give 400,000 low-income students the ability to escape the poorly performing public schools that have failed to educate them. At the same time, it frees high-performing charter school systems from the burdensome regulation now necessary to start up new schools. In Florida, Governor Rick Scott is also innovating to help the state. Scott talks often about competition among the states and has moved to make Florida more competitive. No state can ever “win” all the jobs, but when states compete, businesses and employees are the winners.

P.P.P.S. We are in the process of evaluating many of our equity ETF positions. For a variety of reasons, which I will outline next month, we are looking to further increase our exposure to individual dividend-paying securities and reduce the number of equity ETFs.